Grade: 7-10Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies

Number of Lessons/Activities: 4

Within the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, the issue of sovereignty and self-determination are unique to Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. In this lesson, students will learn about the complex relationships of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders with U.S. citizenship. Students will be introduced to the histories of Hawaiʻi, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa and their current relationships with the United States. Students will also discuss art as storytelling and create an art piece to tell the story of a Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander organization or individual as it relates to sovereignty and/or self-determination.

In what ways are the challenges and experiences of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders related to self-determination impacted by the lack of and/or the prospect of U.S. citizenship?

Students will:

- Explore the complex relationships of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders with self-determination and U.S. citizenship and analyze how each interacts with their peoples’ histories, cultures, and futures.

Citizenship and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Sovereignty Essay:

Background:

Within the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, the issue of

sovereignty and

self-determination are unique to Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, for whom the United States is an occupying nation, similar to other indigenous peoples across the current U.S. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders deal with issues that non-native communities do not, such as

desecration of ancestral sites, militarism, and inaccessibility to natural resources due to colonization. The type of territory – whether incorporated or unincorporated, and organized or unorganized – impacts the relationship of the U.S. to each respective territory and its people. All five permanently inhabited territories are unincorporated, meaning only part of the U.S. Constitution applies to their peoples. Of the five permanently inhabited territories, all except American Samoa, are organized and accordingly have their own local governments and the people born there are U.S. citizens.

Three other nations – Republic of the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, and Republic of Palau – were previously under U.S.

trusteeship (following World War II, until the 1980s) and are now sovereign nations that are in a Compact of Free Association with the United States. Through this agreement, they are independent nations but the U.S. is responsible for their defense, has special access for military operations in these nations, and provides some economic assistance to the nations.

Essay:

The territories in the Pacific Islands and Hawaiʻi have different statuses and, accordingly, different relationships with the United States.

Hawaiʻi

Before Hawaiʻi became the fiftieth U.S. state, it was an independent kingdom, unified by King Kamehameha I in 1810. The Hawaiian Kingdom had several agreements with other nations that established diplomatic and trade relations, including with the United States. Over the course of the mid-late 1800s, the influence and power of U.S. investors and sugar planters grew significantly. In 1891, Queen Liliʻuokalani, sister of the late King Kalakaua, became the monarch and replaced the existing so-called Bayonet Constitution of 1887, advanced by the white American business class to benefit white men at the expense of Native Hawaiians and Asian immigrants, with another constitution that increased the Hawaiian Kingdom’s authority.

In 1893, American sugar planters launched a coup and overthrew Queen Lili

ʻuokalani under the threat of U.S. military force. Anti-

annexation efforts by Native Hawaiians – including a mass petition drive that gained signatures opposing annexation from over half of the Native population, months of lobbying in Washington, and even a failed rebellion – and disagreements in Washington, D.C. delayed annexation for several years. Then, in 1898, the Spanish-American War increased Hawai

ʻi's value and geographical significance as a mid-Pacific U.S. military location. Hawai

ʻi was annexed that year and became the fiftieth state in 1959.

Not all Hawaiʻi residents wanted or celebrated statehood. The Native Hawaiian sovereignty movement continues to seek to reclaim the lost land and culture of the native people. Although recognized by the United Nations in 1946 as a non-self-governing nation, the Admission Act (Hawaiʻi Statehood) in 1959 removed Hawaiʻi from that designation, hampering greater international recognition of the Native Hawaiian sovereignty movement.

Guam

Guam has been colonized for almost 500 years between Spain, the United States, and, briefly, Japan. The U.S. formally acquired Guam from Spain as part of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Spanish-American War and also gave the U.S. the Philippines and Puerto Rico. After the transfer of colonial authority to the U.S., Guam was placed under the jurisdiction of the Navy and was ruled by military governors who had absolute authority over the island’s affairs.

In 1901, a series of Supreme Court rulings known as the Insular Cases determined that U.S. territories could possibly never be incorporated into the country as states. Accordingly, they would receive only limited “fundamental” Constitutional protections and be governed by the U.S. indefinitely. Like Native Hawaiians, the native people of Guam, the CHamoru, resisted against this territorial status and governance by the United States, agitating them for self-determination instead. In 1901 and 1936,

delegations of CHamoru petitioned the U.S. to end their rule over the island and to grant CHamoru citizenship, respectively. In both cases, the U.S. did not grant their petitions, instead, abiding by what the naval administrators of Guam preferred.

Following World War II, the Organic Act of 1950 was passed to cement Guam’s status as an unincorporated territory, creating a non-military, civil government for the island while simultaneously maintaining U.S. power over the island. The Act was passed to pacify the islanders after the Guam Assembly participated in a mass walkout in response to the Naval Governor helping an American violate a law prohibiting Americans from owning local businesses. The Act granted residents of Guam an unequal citizenship status: receive limited Constitutional protections, have no voting representation in Congress (Guam’s delegate to the House of Representatives cannot vote on the final passage of legislation), and unable to vote in federal elections. An amendment to the Organic Act in 1968 created popular elections for the governor, a position previously held by naval, military, and U.S. President-appointed governors. Today, the U.S. military controls about one-third of all land on Guam, and the island continues to have significant military value due to its proximity to Asia.

Northern Mariana Islands

Under Spanish occupation, the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam were a unified territory; splitting in 1899 when the U.S. took Guam, and the rest of the islands were taken by Germany. In 1947, following the end of World War II, the Northern Mariana Islands – under Japanese authority prior to and during part of WWII – were transferred to U.S. trusteeship by the United Nations. Initially, the U.S. Navy was given responsibility for civil administration, but responsibility was transferred to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior in 1951. In 1969, the various trustee territories began political status talks with the U.S., leading to the Northern Marianas holding a

plebiscite in 1975. Through the plebiscite, the people of the islands voted for U.S.

Commonwealth status. Some aspects of the new status were implemented in 1976, including the operation of a new government under its own constitution and an elected governor. The new status as a Commonwealth, effective in 1986, granted U.S. citizenship to eligible residents. In 2008, the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) elected its first delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. However, like Guam’s Representative, the CNMI Representative has limited powers, able to introduce legislation but only vote in committees, not on the final passage of legislation.

American Samoa

In 1899, Samoa was divided in two: Germany gained control of the western islands, and the United States gained control of the eastern islands, eventually named American Samoa. The U.S. Navy held administrative power from 1900 to 1951 and prioritized creating a strategic naval base on the islands, leaving little power to Samoan leaders. After 1951, control shifted to the U.S. Department of the Interior and a governor with full powers to administer the territory was appointed by the U.S. government. American Samoa was not provided an organic act to establish a local government, but was instead granted the authority to write its own constitution. Popular election of governors began in 1977, and the first non-voting American Samoan delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives was elected in 1981.

As an unorganized territory, Samoans have been able to press for and gain more self-determination over their lands and political institutions because they are

non-citizen nationals who are not subject to U.S. judicial oversight and abide by the U.S. Constitution. Their 1967 constitution and 1976

referendum incorporate indigenous customs of life, with two important and unique features of the constitution including communal land ownership and legislature that incorporates Samoan customs. American Samoa’s bicameral legislature also incorporates Samoan traditions: while the House of Representatives is elected, the members of the Senate are chosen by councils of chiefs. The Samoan way of life, or

fa’a Samoa, is communal, and land ownership is determined accordingly: a large proportion of the islands is made up of communal land, which can be owned, sold, and developed only within Samoan families including neighbors, cousins, and other close relations. This communal land ownership system prevents non-Samoans from buying property in a free-market, private property model, as acquiring land also requires people to be at least 50% Samoan.

While some American Samoans, especially those who have moved to the mainland U.S., Hawaiʻi, or Alaska, believe that citizenship should be extended to Samoans, there are many who disagree and believe that U.S. citizenship would jeopardize the sovereignty they have been able to maintain. The American Samoan government has argued that “the imposition of birthright citizenship would upset a political process that ensures self-determination.” For example, prohibiting land ownership based on race would be unconstitutional based on the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause; yet, this is an ancestral custom and practice for Samoans. Many Samoans argue that a closer relationship with the U.S., as a state or organized territory, could lead federal judges to rule the Samoan political system and land rights as unconstitutional and create the possibility of vast demographic and political changes to American Samoa.

Bibiliography:

- Annexation: a formal act whereby a state proclaims its sovereignty over territory hitherto outside its domain

- Commonwealth: a political unit having local autonomy but voluntarily united with the United States; this term is used officially by Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands

- Delegation: a body of persons who are chosen or elected to vote or act for others

- Desecration: the act of treating something sacred or solemn in a sacrilegious or disrespectful way

- Non-Citizen Nationals: persons who are not citizens of the United States but owe permanent allegiance to the United States*

- Plebiscite: a vote by which the people of an entire country or district express an opinion for or against a proposal, typically used for the issue of self-determination; outcome may or may not be legally binding

- Referendum: the principle or practice of submitting to popular vote a measure passed or proposed by a legislative body or by popular initiative; the outcome is legally binding

- Self-Determination: the process by which a country determines its own allegiances and government; the ability to determine one’s own future in their own way

- Sovereignty: the right or authority to self-govern

- Trusteeship: in the context of the United Nations, trusteeships were set up to promote the welfare and advancement of native inhabitants in non-self-governing territories toward self-governance or independence by temporarily entrusting administration of those territories to United Nation members, such as the United States

- What are some commonalities across the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander experiences presented in the essay?

- Why might the U.S. hesitate to incorporate these territories as states? Why might the U.S. hesitate to relinquish its authority over these territories?

- Should all peoples have a right to self-determination?

- Do you think there are situations or instances in which it is okay to impede upon the self-determination of a community or nation? Explain.

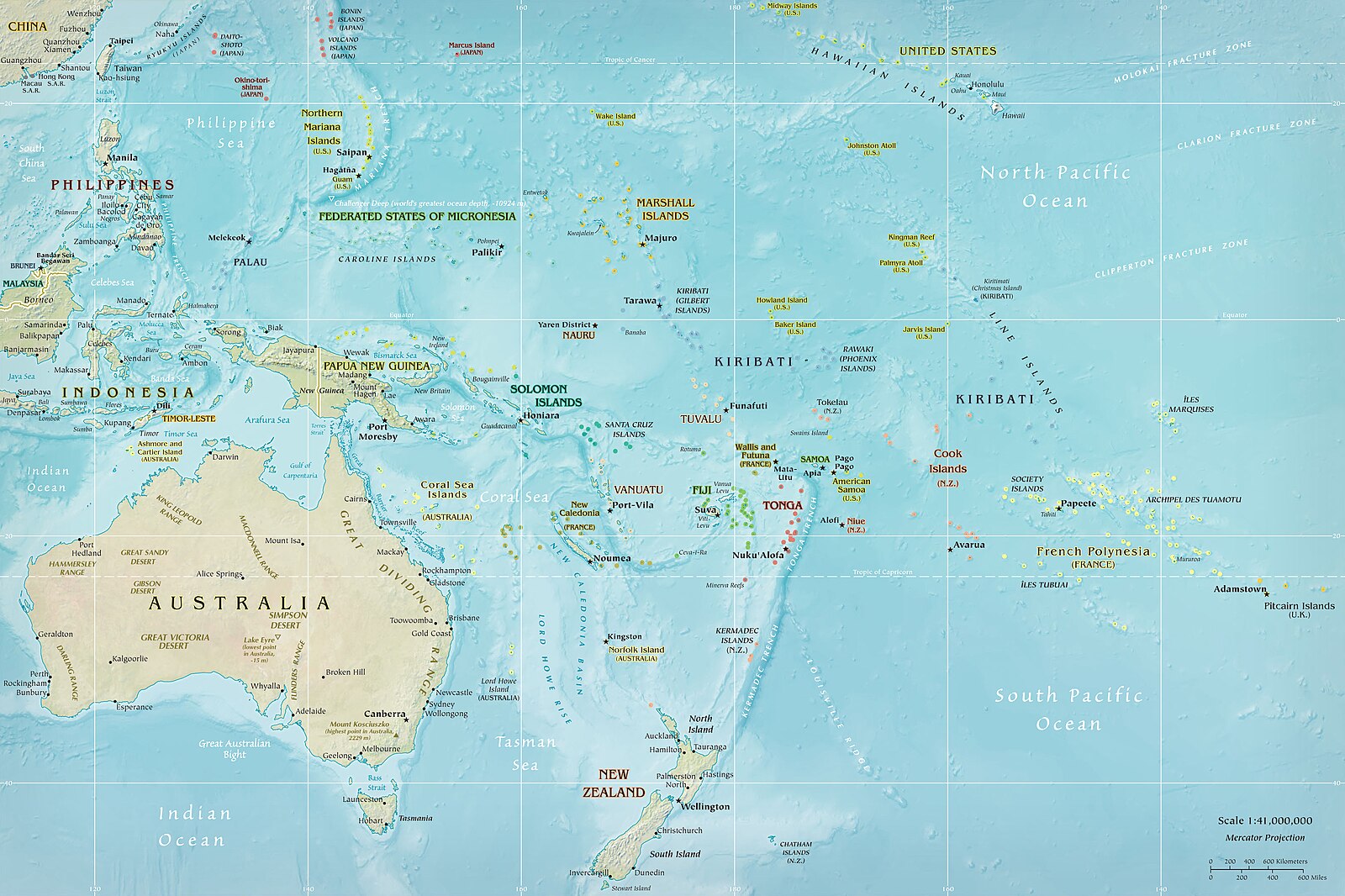

This map of Oceania shows the Hawaiian Islands and the U.S. territories Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa.

Credit: CIA World Factbook via Wikimedia Commons

Activity 1: Understanding Sovereignty and Self-Determination

- Write the words “sovereignty” and “self-determination” somewhere that all students can see. Ask students what they know about these words/concepts, and write their responses on the board. Ask students why they think these words/concepts are important.

- Share the following definitions with students:

- Self-Determination: the process by which a country determines its own allegiances and government; the ability to determine one’s own future in their own way

- Sovereignty: the right or authority to govern one’s own community, people, or nation

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Citizenship unit: Remind students that citizenship in itself does not guarantee freedom and justice. (Support students in connecting this statement to the case of Mamie Tape, Japanese American Incarceration, post-9/11 surveillance, etc.) So far in this unit, citizenship has been discussed primarily from the mainland-U.S. and Asian American point of view. However, for some groups, citizenship may not be what they seek; instead, they want sovereignty and self-determination, as is the case with some Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders, since their land and authority were taken away from them by the United States. As such, they have a different relationship to the U.S. in comparison to the relationship of Asian Americans to the U.S., who primarily came to this country as immigrant and refugee settlers.

- Give students an opportunity to respond, react to, and question this information.

- Inform students that the U.S. currently has a total of fourteen territories. Nine of these are small uninhabited islands, atolls, and reefs. The other five have permanent inhabitants and are under U.S. authority. They are treated as part of the U.S. in some ways, with the U.S. Constitution only applying partially to those in the territories. The five territories are American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Tell students that this lesson will focus on Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and so Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands will not be discussed.

Activists in the Protect Mauna Kea movement have been fighting to protect their sacred land by stopping the development of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on the mountain’s summit. As of 2023, there are thirteen large telescopes on Mauna Kea, an inactive volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi.

“Telescopes on Mauna Kea at sunset” by Brian Harris via Flickr (Public Domain)

Activity 2: History of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Sovereignty

- Have students read the essay about Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Sovereignty (see worksheet entitled, “Essay: Citizenship and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Sovereignty”).

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If you have limited classroom time, have students complete the reading as a homework assignment the night before you implement this lesson.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits and if students need more support, watch the video in and/or implement The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement”: https://asianamericanedu.org/3.3-Native-Hawaiian-Sovereignty-lesson-plan.html. In this lesson, students will learn about the history of Hawaiʻi becoming a U.S. state, from the overthrow of the kingdom to statehood nearly seven decades later. Students will learn about how the Asian American population of the island impacted this trajectory and how Native Hawaiian reacted and responded to the shifting economic and political dynamics.

- Facilitate a discussion about the essay using the Discussion Questions.

- Have students read the article entitled “Mauna Kea Protests: Native Hawaiian Activists Are Fighting for Their Sacred Land.” Explain to students that art as storytelling is one powerful way that communities and individuals share their histories, experiences, perspectives, and teach lessons. Consider how art - across various mediums - can tell a story that might be more impactful than a more direct, explanatory way of sharing the same message or information.

- Divide students into groups of 3-4 and have them engage in discussion about the article. Then, facilitate a class discussion, allowing students to clarify and/or expand on their responses. Provide them the following prompts:

- What was Kapulei Flores’ vision? How does it relate to ancestral knowledge?

- How does Kapulei center cultural respect in her work?

- How can art as storytelling be used to build a movement and discuss serious issues?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: This activity assumes that students have had practice identifying and analyzing elements of writing and art, such as tone, style, etc. If needed, review these elements as a class before students begin the activity.

Left - Hagåtña, the capital of Guam

Center - Mount Tapochau in the Northern Mariana Islands

Right - Beach on Ofu Island, American Samoa

Activity 3: Art and Storytelling

- Distribute the worksheet entitled “Art & Storytelling Worksheet” to students. Working in pairs, have students pick and research an organization/group or individual from (or with ancestry from) Hawaiʻi or the discussed territories to complete the worksheet. Tell students that they will be using their research to create a piece of art and craft a story around it to depict the experiences and share a key message from their researched organization/group or individual.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students need support finding or choosing an organization/group or individual to research, offer the following list:

- American Samoa: Jackie Faʻasisila (author), Okalani Mariner (activist), Terisa Siagatonu (poet and organizer)

- Guam: Julian Aguon (author and lawyer), Monaeka Flores (CHamoru artist), Prutehi Litekyan/Save Ritidian

- Hawaiʻi: Bernice Akamine (artist and activist), Haunani-Kay Trask (activist and educator), Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana, Shut Down Red Hill

- Northern Mariana Islands: Jacinta "Cinta" Matagolai Kaipat (activist/former House representative), Friends of the Mariana Trench, PåganWatch

- After student pairs have completed their research, provide time for them to create their art piece. Drawing on their research and the discussion on art as storytelling in Activity 2, the art piece should craft a story to depict the experiences and share a key message from their researched organization/group or individual.

- Student presentations: have one-third of the student pairs spread out in the classroom so that each pair has some room around them.

- Tell the other students to pick a pair to visit. Make sure that each presenting pair has at least one student that is visiting them.

- Set a timer for one minute, and have the student pairs present their art and story to their audience.

- After one minute, tell students to visit a new pair and repeat.

- Thank the student pairs for their presentations and have them take their seats, replacing them with a new set of student pairs.

- Repeat the steps above, having students visit two different presentations before having the last group of student pairs present.

- As a class, facilitate a discussion using the following prompts:

- Were there common themes or messages across the different stories and pieces of art you observed?

- How did the stories and art make you feel? In what ways are these feelings similar to and different from what you feel when you are reading about a topic?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If you would like to spend more time on the student art and storytelling presentations, the above discussion questions can alternatively be used for journaling or a writing reflection.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: As an extension activity, have students pick a Native American group in the mainland U.S. or Alaska to research. Have students research and study a story from the community and compare it to indigenous groups of the Pacific Islands. Have them consider how that story illustrates the Native people’s relationship to the United States government, the impact of that relationship, and whether/how themes of sovereignty and self-determination appear.

- Assign students the following task for homework as an assessment: “In one page, explain the importance of self-determination for indigenous communities, such as Native Hawaiians, CHamoru, Samoans, and Carolinians. Use at least one specific example to expand upon and support your argument.”

Activity 4: Reflecting on Indigenous Sovereignty

- Read the following quote to students: “We have every right to be angry. We have every reason to be angry. And we ARE angry. And the reason that we're angry – the reason we are angry – is because this is OUR country, and they took our government and imprisoned our queen – right here she was imprisoned in her palace. And they banned our language. And then they forcibly made us a state of the racist, colonialist United States of colonial America. Do you have a right to be angry? Of course you do. Of course you do!”

- Explain that this quote is from the late Haunani-Kay Trask (1949-2021), a Hawaiian activist, educator, author, and poet. She was a leader of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, pressing for Indigenous sovereignty, and helped found the academic field of Hawaiian Studies.

- Have students journal about their reactions to the quote, and the quote in context of what they’ve learned about indigenous communities in the Pacific. After students have been able to journal for a few minutes, facilitate a class discussion on their reflections and reactions.

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Citizenship unit: Have students make a list of the top three things they have learned from this unit. Have students make a list of the top three things they would like to learn more about.