Grade: 7-10Subject:

History, Social Science

Number of Lesson Days: 3

Throughout American history, public education has had to wrestle with questions about who gets educated and how they get educated. As the United States expanded and diversified, it became evident that not everyone had the same access to education. In this three-day lesson, students will learn about how public education has been used as a tool for assimilation for a common American culture and language. On Day 1, students will be introduced to stereotypes that have impacted Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. On Day 2, students will discuss the purposes of education and how public schooling and the learning of English has impacted Asian Americans. On Day 3, students will analyze primary and secondary sources related to Chinese American-led school desegregation court cases.

What role did public education play in the lives of early Asian Americans?

Students will analyze primary and secondary sources related to the Tape v. Hurley (1885) and Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson (1971) cases in order to ascertain and examine the role public education played in the lives of early Chinese American immigrants.

Assimilation through Schooling Essay

Background:

In early U.S. history, schooling was largely provided at home or through religious institutions. But as the First Amendment and state laws separated church from state, there was a need for non-religious, public education. Over time, public education has had to wrestle with questions such as who gets educated and how they get educated. As the United States expanded and diversified, it became evident that not everyone had the same access to education. Marginalized groups including communities of color, disabled persons, and English Language Learners, have had to fight for accommodations and/or equal access. Early Asian immigrants faced issues of racism, sexism, and classism. In addition, being seen as “perpetual foreigners,” they faced discrimination as non-native speakers of English.

Essay:

The goals of a free, public education are to create productive citizens of the nation and to help unify the different people and regions in the United States into a more uniform national body. However, the underlying racism and

nativism of those in power has impacted this vision of education.

It was believed that having a basic, common education would instill shared values. However, whose values are being taught? And in whose language? Unofficially, American English is the most commonly used language in the United States. It is also the language used in schools. Public education in the United States was created for

assimilation. It was created to teach and foster a common American culture and language. This is especially true for non-white and non-English-speaking communities.

Through public education, children not only learn English and math, but also “American” manners, customs, and culture in order to fit into U.S. society. The culture promoted was the white,

Anglo-Protestant culture, since they held the most power in early U.S. society. (And arguably still hold the most power.) Accordingly, the systems and structures that were created for public education incorporated white Anglo-Protestant attitudes and beliefs.

The foundation of the United States is rooted in

white supremacy. As such, people of color were considered inferior to white people in aspects like their intelligence, appearance, beliefs, customs, and more. Education was thus seen as a key way to “Americanize” immigrant and non-white children, who looked and acted differently from prevailing images of an “American.” White supremacist thinking has led to many racist laws and policies.

In addition to racism, early U.S. society was also anti-immigrant, specifically immigrants of color. This is evidenced by anti-exclusion laws that banned Asians from immigrating to the United States. Public education reflected national politics. As such,

racial segregation in schools was common across cities and states in the United States. Those who supported segregated schools argued that different races were too different to learn side-by-side. More plainly, white people who supported segregated schools didn’t want their children mingling and interacting with non-white children.

But communities of color, including Asian Americans, challenged racial segregation. For many, education was seen as the key to

social mobility. Being able to speak the language of power and act like the culture in power were necessary for social success.

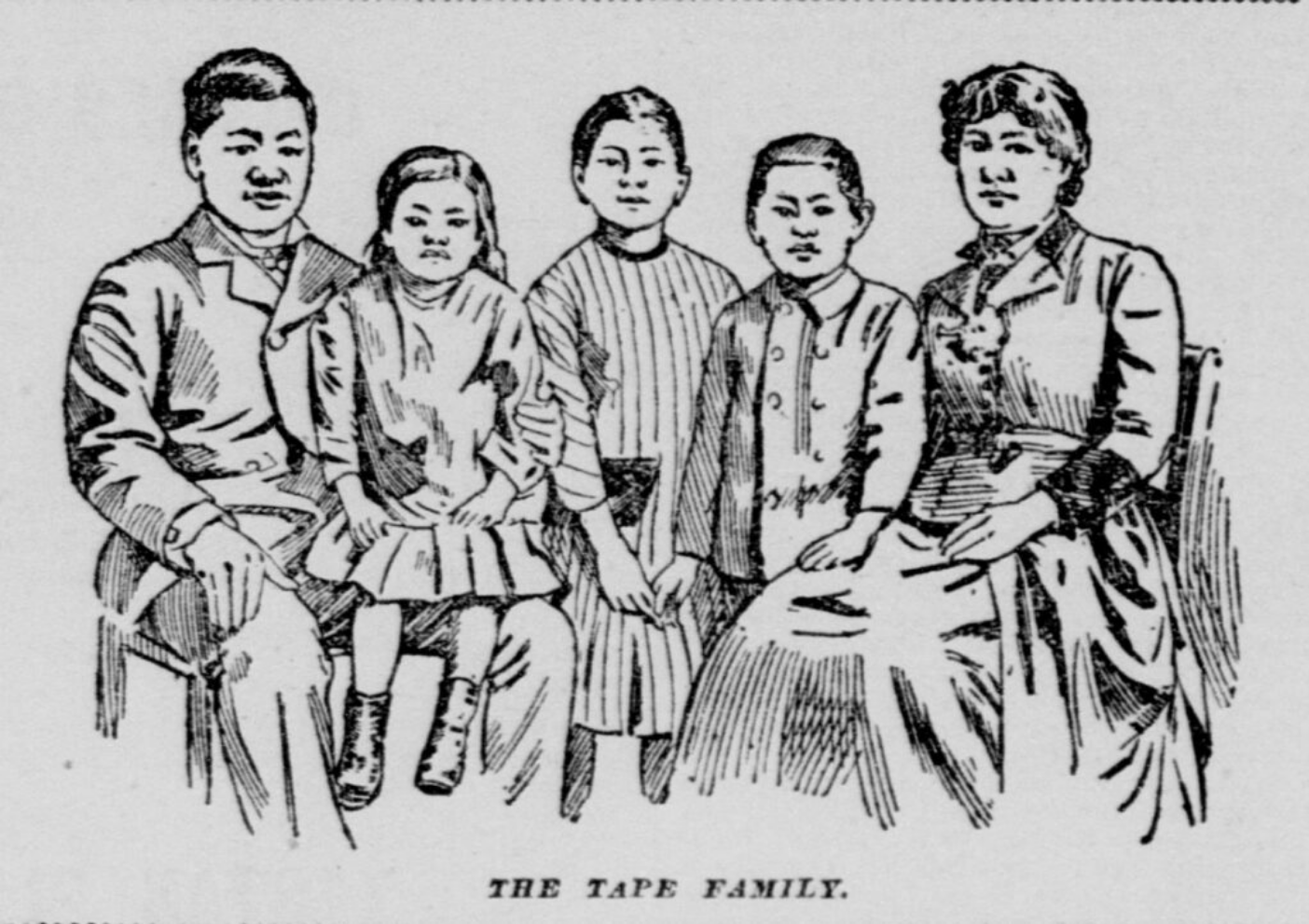

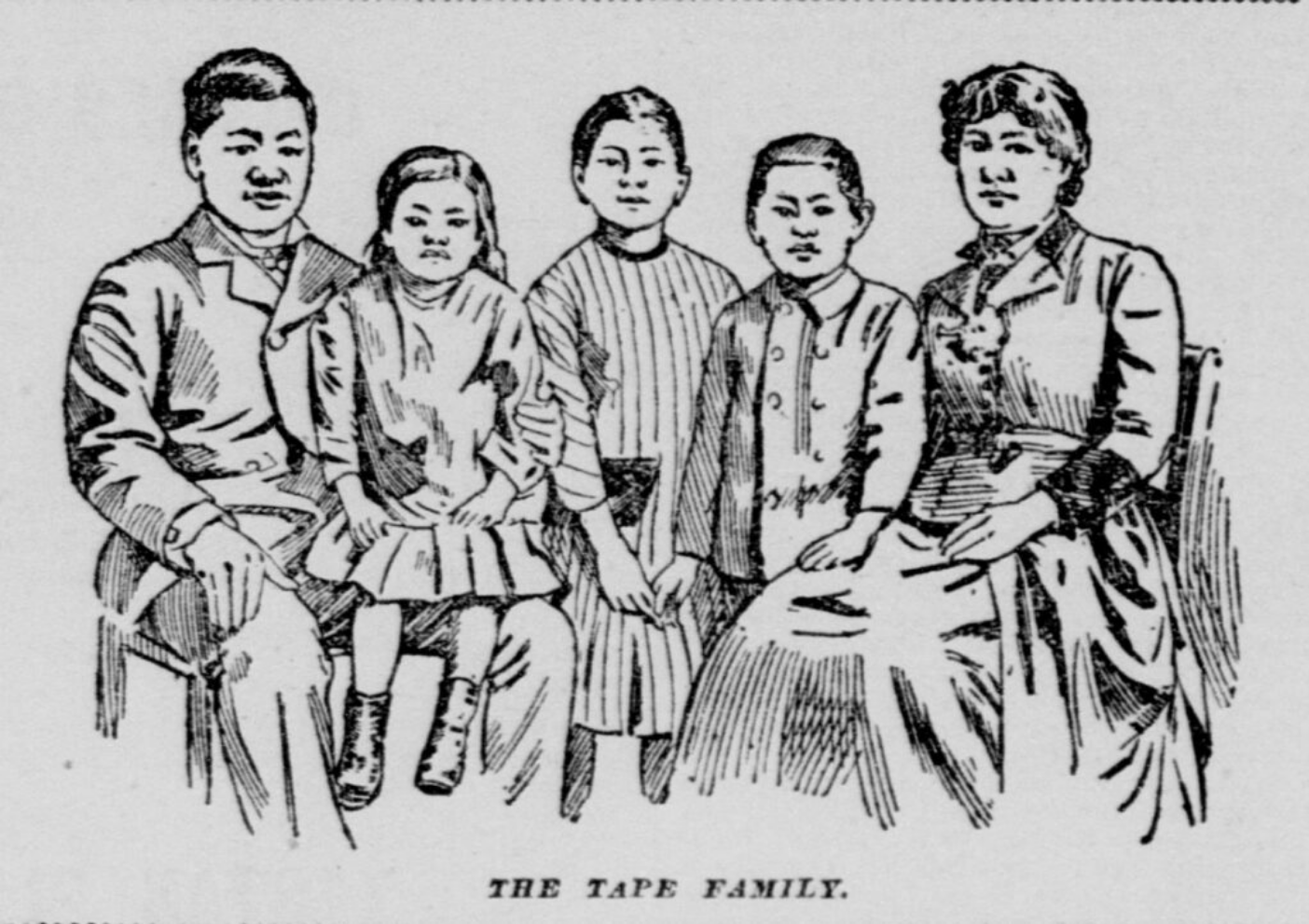

One notable example is the landmark case, Tape v. Hurley (1885). In California in the 1880s, the Tape family legally challenged the San Francisco Board of Education when their daughter Mamie Tape (1876-1972) was denied access to public education. Joseph and Mary Tape (1857-1934) were Chinese immigrants who had lived in the United States since their early teenage years. The Tapes considered themselves as American as any of their white neighbors. They believed Mamie, who was born in the United States, should be allowed to attend the all-white Spring Valley Primary school. But Mamie was denied enrollment due to her race. In response, the Tapes sued the school principal, Jennie Hurley, and took the case to the California Supreme Court.

The case was one of the earliest

civil rights decisions against racist segregation policies. School officials argued that people of Chinese descent shouldn’t be admitted to San Francisco public schools since the California Constitution stated the Chinese were “dangerous to the well-being of the state.” The Court ruled that the

Fourteenth Amendment protected Mamie’s right as a U.S. citizen to attend school. At the same time, however, the Court suggested that segregated schools weren’t against the law. This led the San Francisco Board of Education to quickly build separate schools for Chinese students, where the Tapes had to enroll their children later that year.

In another notable case in Mississippi in 1927, a Chinese family, the Lums, fought for the rights of their daughters, Berda (c. 1914-?) and Martha (c. 1915-?), to attend an all-white school. Like Mamie Tape, Berda and Martha had been removed from school after the first day due to their race. The Lum family fought the dismissal and took the case all the way to the Supreme Court in Gong Lum v. Rice (1927). The Court however ruled to uphold segregation, citing that the State’s constitution called for separate schools for white and “colored” students.

This concept of “separate but equal” schools was upheld by the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) ruling. At this time, segregated schools were not perceived to be illegal. Historically, communities of color, denied access to white-only schools, were forced to create their own schools. Often, these segregated schools for people of color were overcrowded and had fewer resources than the white-only schools. They were separate but they were far from equal. For communities of color seeking social mobility, such inequities were intolerable.

Decades later, five Mexican American families in Southern California came together and successfully challenged discriminatory segregation based on ancestry and language ability in

Mendez v. Westminster (1947). While the case, like

Tape v. Hurley, didn’t end racial segregation, it set a

precedent for later cases, like

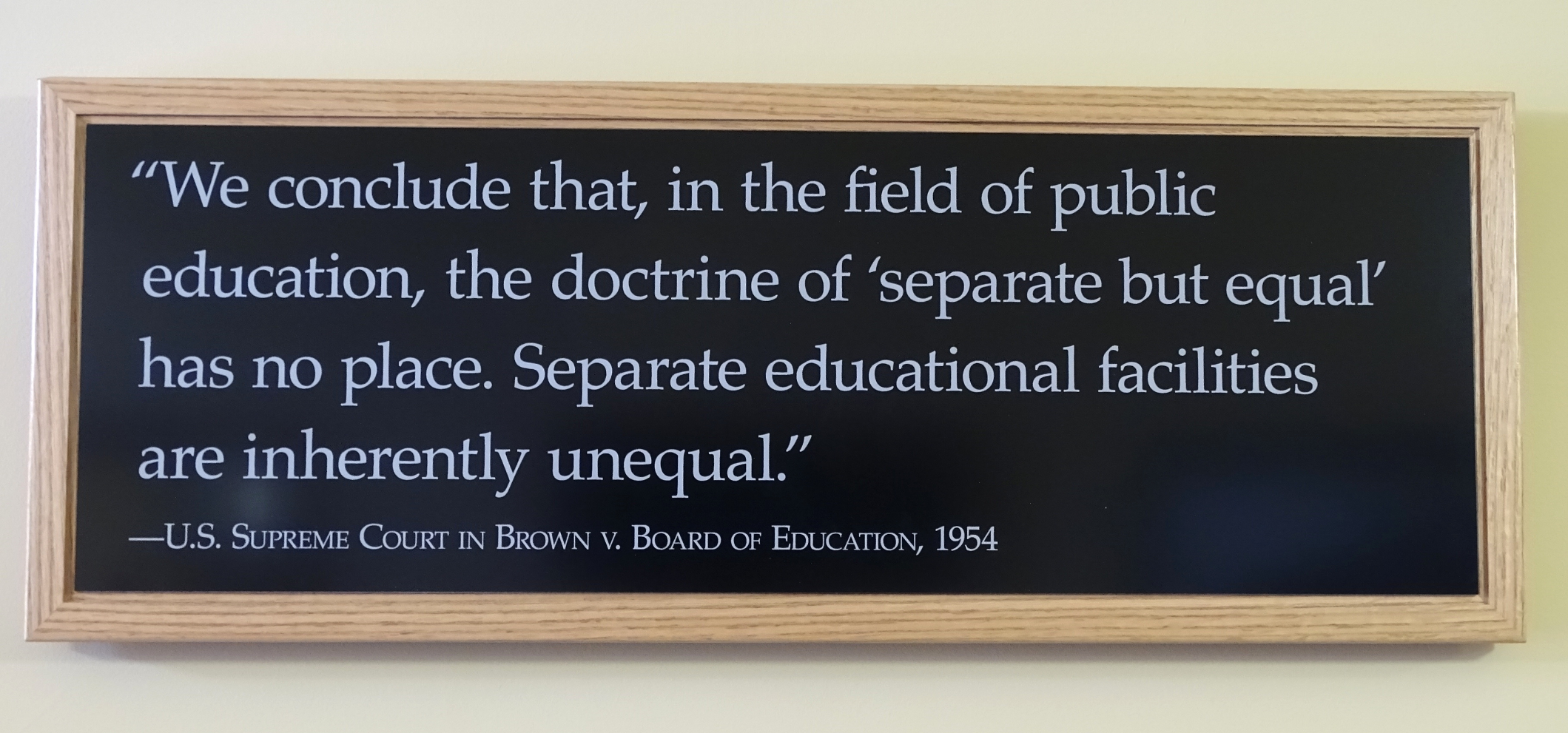

Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which found school segregation based on race unconstitutional.

Finally, the case of

Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson (1971) presented a different perspective on segregation. In response to

desegregation efforts in the San Francisco Unified School District, some Chinese parents protested the move and sued. They wanted their children to stay in Asian segregated schools, fearing their children would face racism and lose their cultural heritage and language. But the court denied their pleas. The district’s desegregation plan moved forward. The ruling stated that

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) extended to all racial minorities discriminated against by the State, which included the Chinese in California. The ruling additionally stated that courses teaching cultural background and heritage of various racial and ethnic groups and bilingual classes were not forbidden, and so those could be created in any manner that did not create or replicate segregation.

The case of Lee v. Johnson (1971) demonstrated struggles faced by many communities of color. Communities of color are pushed and pulled in different directions. They have the desire to assimilate for social mobility, but also feared the loss of their language and culture. This tension continues today.

Bibiliography:

- Anglo-Protestant: upper class white social group

- Assimilation: process through which individuals/groups of differing heritages acquire attitudes, habits, and mode of life of a dominant culture

- Civil Rights: set of fundamental rights for everyone

- Desegregation: the policy of ending the separation of races

- Fourteenth Amendment: granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and guaranteed “equal protection of the laws”

- Nativism: attitude or policy where existing inhabitants are favored instead of immigrants

- Precedent: an event or action that’s an example or guide for future similar situations

- Racial Segregation: separation of a racial group by forced residence in a certain area, barriers to social intercourse, and other means

- Social Mobility: the ability to change one’s social status for the better

- White Supremacy: social, economic, and political systems that collectively enable white people to maintain power over people of other races

- In what ways did U.S. schools assimilate or “Americanize” students?

- How and why were Asian Americans (and other communities of color) excluded?

- In what ways were Asian Americans seen as “perpetual foreigners” and how did that impact their treatment?

- If schools are tools for assimilation, then why were certain groups of people denied access to them?

- How did Asian Americans challenge racist segregation?

- As evidenced by the Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson (1971) case, what concerns might Asian Americans have about an American education?

Activity 1: Introduction to the Unit

- Explain what it means to be Asian American and/or Pacific Islander (“AAPI”):

- Inform students that there are different identifiers for the AAPI community: Asian American, AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander), AA & PI (Asian American and Pacific Islander), AANHPI (Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander), APIDA (Asian Pacific Islander Desi American), etc.

- Explain that these identifiers are used to describe the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities which represent many unique cultures, heritages, and histories.

- Explain that the term “Asian American” was first coined in the 1960s as a social and political identity to reject racist terms previously used to identify this group. It was also used to create unity and solidarity among various AAPI groups.

- Explain how it is important to recognize the unique identities within the larger identifier and to not see AAPI people as a monolith.

- Explain that over the course of the unit, there are moments when “Asian American” is used instead of “AAPI.” This is a purposeful choice to not conflate Pacific Islanders with Asian Americans by using “AAPI” if they are not actually the focus of, or included in, the topic at hand. Similarly, there are moments when “Pacific Islander” is used for the same reason.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Skip this lesson and go straight to Day 2 if your students already have a basic understanding of the Model Minority Stereotype and the Perpetual Foreigner Stereotype.

Activity 2: Introduction to Stereotypes

- Ask students: What is a stereotype? Have you ever experienced stereotyping?

- Allow students an opportunity to share their responses.

- Create a T-chart with “What is a stereotype?” on the left side, and “What are the impacts of stereotyping?” on the right side.

- As students share, write relevant responses in the T-chart.

- Review contents of T-chart and ask students: In what ways are stereotypes harmful?

- Share the following statement: “The two stereotypes that have plagued the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities are the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner stereotypes. Both of these stereotypes have influenced their experiences in the United States. In addition, both of these stereotypes have prevented Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders from feeling a full sense of belonging in the United States.”

Photo of an individual holding a sign that says “Not your model minority.”

Activity 3: Introduction to the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner Stereotypes

- Distribute the worksheet entitled “Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner.”

- Complete the first row with students, answering the questions, “What is it?” - Have students write down the responses as you explain them:

- Model Minority: The Model Minority stereotype is the notion that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are “smart” and “hardworking.” They have achieved success through hard work and determination and are suitable models for other minorities to emulate.

- Perpetual Foreigner: The Perpetual Foreigner stereotype is the idea that Asian American and Pacific Islanders are foreigners because of their appearance, language, and customs, etc. They will always be seens as outsiders no matter how long they have lived in the United States or whether they’re American-born.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students need more support in understanding Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner stereotypes, consider teaching these lessons (or relevant parts of the lessons) from The Asian American Education Project: (1) “Perpetual Foreigner - Systemic Racism Against Asian Americans”: https://asianamericanedu.org/perpetualforeigner.html; and (2) “Model Minority Myth”: https://asianamericanedu.org/3.1-Model-Minority-Myth-lesson-plan.html

Activity 4: Researching the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner Stereotypes

- Have students work in small groups to complete the rest of the worksheet entitled, “Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner.” Have students use the internet to research and answer the following questions:

- How did the stereotypes originate? What truths are behind the stereotypes?

- In what ways is it incomplete or inaccurate?

- How does it negatively impact the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities in society?

- How does it negatively impact the Asian American and Pacific Islander community in schools?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If pressed for time, have some groups research Model Minority and other groups research Perpetual Foreigner. Or, instead of having students work in groups, turn this into a presentation using the Answer Key as lecture notes.

- Review and discuss responses. (See Answer Key.)

Activity 5: Diversifying Our Idea of “American”

- Show the video entitled, “I am an American”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rne_jxxIbas&t=9s

- Facilitate a discussion by asking students the following questions:

- What message is the video trying to convey?

- Why is it important to diversify our idea of an “American”?

- Why is it important to not see Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders as “foreigners”?

- Share the following statement: “In regard to cross-cultural solidarity, the Perpetual Foreigner stereotype positions Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders as outsiders, unassimilable, and foreign. Such thinking allows for policies and laws that promote exclusion and create a wedge between Americans and non-Americans. In addition, the Model Minority stereotype more directly creates a racial wedge by suggesting that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the exception and have been able to achieve in spite of various barriers. It essentially says that the achievement of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders is proof that the system is not the problem, placing the blame on other minority groups for not achieving. Both stereotypes are problematic because they serve to separate communities of color and prevent them from coalescing to fight against white supremacy. Pitting communities of color against each other is a strategy that maintains the status quo and prevents liberation and justice for all groups. As such, any form of racism is bad for any and all groups affected by white supremacy: racism can make any group an ‘other’ and create false rifts between groups that are all impacted by racism.”

- Tell students to refer to these concepts of Perpetual Foreigner and Model Minority throughout the unit. Explain how perceptions about Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have impacted how they have been treated in society-at-large.

NOTE TO TEACHER: This lesson/unit focuses more on the Chinese American experience as they were the first large Asian population to settle in early U.S. history, meaning they were the first to engage in direct actions against racist U.S. institutions. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have made significant contributions; but because of the limited time we have in this unit, we cannot cover all topics and all groups. That being said, because all Asians in the United States tend to be seen as a monolith despite having vastly different languages and cultures, Asian immigrants (regardless of ethnic heritage) received mostly the same treatment and faced many of the same challenges. That stated, please remind students that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders consist of diverse and unique communities with their own rich cultures, languages, and histories.

Quote from the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision.

Credit: “Quote on Segregation from Supreme Court Decision - Brown v. Board of Education Historic Site - Topeka - Kansas - USA (40940562055)” by

Adam Jones,

CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Activity 1: Purpose of Education

- Have students complete a Quickwrite given these prompts: Why do you attend school? What role does education play in your life? What are your goals and how will an education help you meet these goals?

|

Strategy: Quickwrite

A Quickwrite is an instructional practice that allows students an opportunity to quickly respond to a question or prompt. It is often timed for 3-10 minutes. It provides teachers an assessment of what students know or think at that moment in time. It provides students an opportunity to freely write down their first thoughts. It can be used at any time in a lesson.

For more on Quickwrites, see:

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share what they wrote in their Quickwrites.

- Ask students: What is the purpose of public education? Record and display student responses for all to see.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: In considering the purposes of education, student responses may vary. Responses will include: to learn skills or knowledge needed in life; to prepare for college or a job; to open up new opportunities/social mobility; to teach U.S. culture and customs; to teach English; to shape young people; to learn how to work with diverse people and mindsets, etc.

- Facilitate a discussion about why and how the purposes of education change. Ask these questions:

- In what ways do the purposes of education change as you grow older?

- In what ways do the purposes of education change for different groups of people?

- In what ways have the purposes of education in the United States changed over the course of history?

- What accounts for these changes?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Ensure students understand that the purposes of education are impacted by politics, personal goals, societal/national goals, racism, classism, sexism, nativism, etc. Stress how education is dynamic and is subject to state and national laws and public sentiments.

- Ask students: What do you know about school segregation? What do you know about Brown v. Board of Education (1954)? How does Brown v. Board of Education (1954) affect us today? Record and display student responses for all to see.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: The assumption is that students have previously learned about Brown v. Board of Education (1954). If not, play the video entitled, “Brown v. Board of Education”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1siiQelPHbQ. Have students take notes during the video, or have students complete a Quickwrite summarizing key points they learned from the video.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Thinking back to our list of the purposes of education, how do segregated schools help achieve those purposes? How do segregated schools serve as a barrier for achieving those purposes?

- Who benefits from segregated schools? Who doesn’t benefit?

- What other thoughts or questions do you have about the impacts of segregation or the purpose of education in the U.S.?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Ensure students understand that segregated schools do not benefit anybody. Even though segregated schools seem to benefit white communities because these schools tend to have more resources, white students are also disadvantaged because they are denied access to diversity and intergroup collaborations which are essential for success in the 21st century. If time permits, have students discuss the concept of “de facto segregation” which is the separation of people that occurs “by fact” or circumstances, rather than by legally imposed requirements, i.e., share how schools today are segregated by neighborhoods.

- Share the following statement: “Most people are familiar with the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) case. But school segregation has also impacted Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Mexican Americans. Before Brown, there was a landmark school segregation case involving a Chinese American family, Tape v. Hurley (1885). This lesson will focus on the experiences of Asian Americans in relation to public education and school segregation.”

Activity 2: Assimilation Through Schooling

- Explain the definition of assimilation, which is the process through which individuals and groups of differing heritages acquire the basic habits, attitudes, and mode of life of the dominant group.

- Distribute the “Assimilation Through Schooling” essay to students. Direct students to read the essay and take notes as they read. Encourage students to note comments and questions in the margins and to highlight or underline key ideas.

- Have students discuss the following questions in small groups:

- What did you learn from reading the text?

- What ideas did you agree with?

- What ideas would you like to challenge?

- What questions do you have? What was confusing to you?

- Allow students an opportunity to share comments from their small group discussions. Answer any questions and provide clarification as needed.

- Facilitate a discussion about the text by asking the Discussion Questions.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits, consider going in depth to discuss the Gong Lum v. Rice (1927) case. While the Lum family was taking a stand against white supremacy through their lawsuit, they were also reinforcing anti-Black racism in their reasoning. In challenging racial segregation, the Lums didn’t want to send their daughters to the Black school in the district. This illustrated the racial hierarchy in place in the United States and how it impacted the Lum family’s understanding of quality schooling. Ensure students understand that racial hierarchy is a system of sorting or classifying society based on the belief that some racial groups are superior to other racial groups; in the United States, “White” is at the top and “Black” is at the bottom. In some cases, Asian Americans have been pitted against the Black community in order to gain white privileges. Today’s Asian American activism is rooted in the notion that abolishing anti-Blackness is key to liberation for all.

Activity 3: Conver-Stations on Public Schooling and Learning of English

- Set up the following questions in each of the four corners of the classroom:

- Corner 1: How is public schooling and learning English used as a tool for assimilation?

- Corner 2: How is public schooling and learning English used as a tool for social mobility?

- Corner 3: How does public schooling and learning English impact culture and language loss?

- Corner 4: How does public schooling and learning English support racism at the systemic level?

- Divide students into four groups and assign them to a corner. Give each group about 3-5 minutes to discuss their assigned questions. When time is up, have half the group rotate to a different corner. Repeat the process. When time is up again, have the other half that didn’t move, rotate to a different corner. Do this several times.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking students to share what they discussed in their small groups.

|

Strategy: Conver-Stations

Conver-stations is a small-group discussion strategy that gives students exposure to more of their peers’ ideas and prevents stagnation. Students are placed into a few groups of 4-6 students each and are given a discussion question to talk about. After sufficient time has passed, a few students from each group rotate to a different group, while the other group members remain where they are. Once in their new group, they will discuss a different, but related question, and they may also share some of the key points from their last group’s conversation. For the next rotation, students who have not rotated should move, resulting in groups that are continually evolving and sharing ideas.

For more on analyzing sources, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If pressed for time, facilitate a whole-group discussion instead of moving students into discussion groups. Focus on the question: How does public schooling and learning English support racism at the systemic level? Explain that systemic racism is the complex interaction of culture, policy, and institutions that disadvantage some groups and privilege others; systemic racism makes it more challenging for marginalized communities (including non-native English speakers) to participate and achieve in society.

Activity 4: Review Purpose of Education Quickwrites

- Revisit the introductory discussion of the purposes of education. Have students reread their Quickwrites.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How are your goals for education similar to the goals of the people mentioned in the text?

- How are your goals for education different from the goals of the people mentioned in the text? What accounts for these differences?

- Tell students the next lesson will go deeper into some of the court cases mentioned in the article.

Activity 1: Assimilation Quickwrite

- Remind students of the definition of assimilation, which is the process through which individuals and groups of differing heritages acquire the basic habits, attitudes, and mode of life of the dominant group.

- Have students complete a Quickwrite given these prompts: Have you ever tried to fit in? Describe the circumstances. Were you successful? Why or why not?

|

Strategy: Quickwrite

A Quickwrite is an instructional practice that allows students an opportunity to quickly respond to a question or prompt. It is often timed for 3-10 minutes. It provides teachers an assessment of what students know or think at that moment in time. It provides students an opportunity to freely write down their first thoughts. It can be used at any time in a lesson.

For more on Quickwrites, see:

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share what they wrote in their Quickwrites.

- Share the following statement: “In every culture, there are in-groups and out-groups. The in-groups have the most power. To be a member of these groups, people need to know the language, symbols, and culture.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- In the United States, who are the “in-groups”?

- In the United States, who are the “out-groups”?

- How and why is speaking English an important part of being in the “in-group”?

- What role does public education play in assimilation?

Drawing of the Tape Family in November 23, 1892’s edition of The Morning Call.

Credit: “The Tape Family,” from The Morning Call, via Library of Congress (Public Domain)

Activity 2: Historical Thinking about Mary Tape’s Letter

- Distribute “Primary Source: Mary Tape’s Letter.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students are unfamiliar with primary sources, take time to define and explain primary sources (firsthand accounts), secondary sources (secondhand accounts; information created from primary sources), and tertiary sources (sources that compile or summarize primary and secondary sources).

- Read the letter as a class. Explain that this letter is a primary source; as such, misspellings, etc., are purposely left in.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits and if students need more support, watch the video in The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “The Fight for School Desegregation by Asian Americans”: https://vimeo.com/685562797

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Historically Thinking about the Tape and Lee Cases.”

- Complete Part I with students by answering the following questions:

- Who wrote this?

- When was it written?

- Where was it written?

- Is it reliable? Why or why not?

- What was happening at the time? Explain the historical context.

- How did the historical context affect the content of the source?

- What claims does the author make?

- What evidence does the author use?

- What language does the author use to persuade the audience?

- How does the language indicate the author’s perspective?

- What does the language tell us about the author?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Model how to refer back to the text for information and how to do further research (via the internet) to answer the questions. Reassure students that some questions may be harder to answer than others due to lack of information.

|

Strategy: Historical Thinking Skills Chart

Historical Thinking Skills Chart is a way to help students contextualize primary and secondary sources. This strategy supports students’ historical reading skills such as sourcing, contextualization, close reading, and corroboration.

For more on Historical Thinking Skills Chart, see:

|

Activity 3: Historical Thinking about the Lee (1971) Case

- Have students read the article entitled, “Chinese Ask Court To Bar Busing Plan For San Francisco.”

- Read the text as a class. Explain that this text is a secondary source; as such, the author may have made interpretations and inferences.

- Have students work in small groups to complete Part 2 and Part 3 of the worksheet entitled, “Historically Thinking about the Tape and Lee Cases.”

- Review responses with students using the Answer Key.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What do the texts reveal about the Chinese American experience with U.S. education?

- What role did public education play in the lives of early Chinese American immigrants?

- What are the goals of public education in the United States and how have these goals been achieved for early Asian Americans? How have they been denied?

- How did Asian Americans resist racist laws and policies? How did they contribute to education?

- Why is it important to know about these cases? What implications do they have for today?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time permits or for homework, have students identify an additional source and write a historical claim that examines the role of public education in the lives of early Asian Americans.

Activity 4: Public Education as a Tool

- Have students write a one-page response outlining the ways that public education was used as a tool by and against Asian Americans. Students should rely on the sources studied over the course of the lesson.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Remind students that they have studied an example of a primary source (Mary Tape’s letter), a secondary source (The New York Times article about the Lee [1971] Case), and a tertiary source (“Assimilation Through Schooling” by The Asian American Education Project).

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Multilingual Education unit: Summarize this set of lessons by sharing this statement: “As we have learned, public education serves many purposes. Asian Americans have been perceived to be perpetual foreigners; as such, education has been used as a tool for assimilation, specifically the teaching of English. Asian American resistance has helped in the desegregation movement. That stated, desegregation brings up challenges regarding language and cultural loss. In this unit, we will learn more about Asian American and Pacific Islander contributions to the development of multilingual education and the tensions and struggles faced by this community in regard to learning English and public schooling.”