4.7.1 - English as a Second Language

The Asian American Education Project

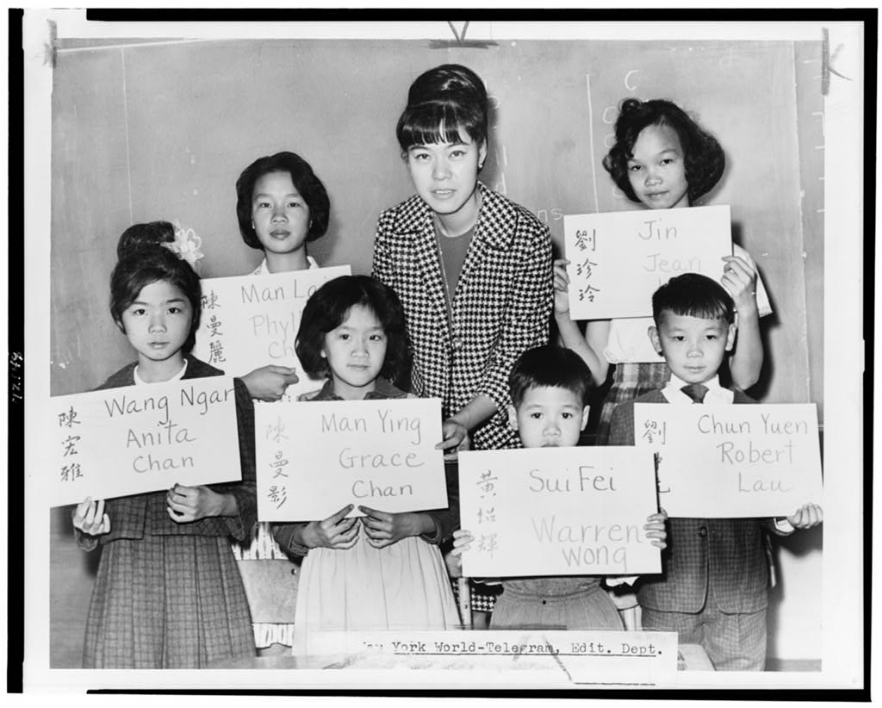

Students holding signs with their names in Chinese and English.

Credit: “[Miss April Lou, teacher at PS 1, Manhattan, with six Chinese children, recent arrivals from Hong Kong and Formosa, who are holding up placards giving his or her Chinese name (both in ideographs and in transliteration) and the name to be entered upon the official school records]” by Fred Palumbo, via Library of Congress (No known restrictions on publication)

Grade Levels: 7-10Subject:

History, Social ScienceNumber of Lesson Days: 3

Language – like other markers of identity – can be political. Due to the meaning attached to speaking English, it has been used in the United States at times to categorize who is an “American” and who is a “foreigner.” In this three-day lesson, students will learn about the history of bilingual and multilingual education in the United States and how court cases and legislation have impacted English Language Learners. On Day 1, students will read text and watch videos to identify enduring issues related to bi- and multilingual education, and the court case Lau v. Nichols (1974). On Day 2, students will learn about another bilingual education case, Aspira v. New York (1975), through summarizing and comparing it to Lau v. Nichols (1974). On Day 3, students will analyze primary and secondary sources to understand the historical significance of Lau v. Nichols (1974).

How and why is the Lau v. Nichols (1974) case significant to public education in the United States?

Students will analyze the historical significance of Lau v. Nichols (1974) in order to ascertain its impact on public schooling and to the fight for civil rights in the United States.

English Language Education Policies in the United States Essay:

Background:

Language – like other markers of identity – can be political. Due to the meaning attached to speaking English, it has been used in the United States at times to categorize who is an “American” and who is a “foreigner.” As racial and social conditions within the United States changed over time, opinions on bi- and multilingual education have shifted as well, ranging from support to hostility in the form of English-only policies.

Essay:

The United States has always been a

bi-/multilingual society, even before it became the nation we recognize today. As early as the 1800s, there were states that endorsed and allowed bilingual education in their schools. Education in a language other than English has existed where ethnic groups were in large enough concentrations to exert some level of power. In early U.S. history this was evident in communities that spoke German, French, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, and other European languages. However, there were also states that passed laws forbidding educational instruction in languages other than English. Additionally, even in the states friendly to bilingual education, Native American youth were forced to attend off-reservation boarding schools. They were forced to learn English and were banned from speaking their native languages.

The Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 sparked a new era of civil rights in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968) was a struggle for equal rights for Black Americans and other communities of color. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, sex, religion, and national origin. Title VI of the Act stated that any program receiving federal funding – which included public schools – could not discriminate against any person based on race or national origin.

During this time, Latinx activists created a strong push for Spanish-speaking bilingual education programs. Through legal cases and

direct action, Spanish-speakers in the United States pointed out the

discrepancies between English-speaking students (usually white) and non-English-speaking students (usually non-white). There was a vast difference in educational achievement and student treatment between the two groups. In addition, there was a vast difference in the quality of education. Non-English-speaking students lacked proper assessments and textbooks. Teachers were also not trained to teach English Language Learners.

There was an increase of Spanish-speaking immigrants settling in Texas and many other southwestern states. As such, in 1967, Senator Ralph Yarborough (1903-1996) of Texas introduced a bill to help school districts educate students with limited English skills. This bill would go on to become the

Bilingual Education Act of 1968. The Bilingual Education Act was the first federal law to recognize English Language Learners as having unique educational needs that could be addressed through more effective education. It also provided school districts with federal funding to create and implement programs to build English fluency. It eventually led to the establishment of bilingual education, which is the teaching of academic content in two languages: English and a native language.

Initially, the Bilingual Education Act did not require bilingual education. It simply focused on programs designed to teach English. Additionally, the Act did not provide any guidelines for school districts who then had to create their own programs. Furthermore, the participation of school districts was

voluntary. As such, English Language Learners across the country were still being neglected. They were not receiving the support they needed.

In the early 1970s, the San Francisco school system in California had almost 2,900 Chinese American students who did not speak English as their first language. Only 1,000 of these students were receiving

supplemental English classes. The remaining students were left on their own – either succeeding or failing in English-only classrooms.

These students and their families gathered to file a lawsuit against the San Francisco Unified School District, claiming that they were not provided with equal educational opportunities, thus violating their

Fourteenth Amendment rights. This case became known as

Lau v. Nichols (1974).

The lower courts initially ruled in favor of the school district, claiming that the students were receiving an education equal to their English-

proficient peers. However, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the students in 1974. The Court argued that providing all students with the same facilities and curriculum is not what constitutes equal treatment. Instead, equal treatment is also based on providing students the tools and support they need to meet education standards. The Court argued that Title VI of the Civil Rights Act had been violated, as schools bear the responsibility of making instruction accessible for students. This means that students need to be able to understand the content of what they are being taught while also learning English, which was not the case for the Chinese American students being denied supplemental English resources or curriculum.

Soon after, in 1974, the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) was passed and the Bilingual Education Act was amended as well. The EEOA stated that educational opportunities could not be denied to English Language Learners. It required “appropriate action” by states to overcome language barriers that obstruct the equal participation of English Language Learners in schools. Both the EEOA and the amendment to the Bilingual Education Act extended the

Lau ruling to all schools, even those that didn’t receive federal funding. They also defined bilingual education programs and inspired the creation of basic guidelines for teaching English Language Learners known as the “Lau

Remedies” (1975). In addition, the Lau Remedies created guidelines to help determine whether a school district was complying with the law.

The Lau v. Nichols (1974) ruling was very significant in recognizing the civil rights of English Language Learners. In San Francisco, where it started, the case inspired a diverse coalition of parents to ensure that San Francisco schools not only complied with the law but also created bilingual programs that maintained students’ native languages in addition to learning English.

There was a shift during this time, as evidenced by

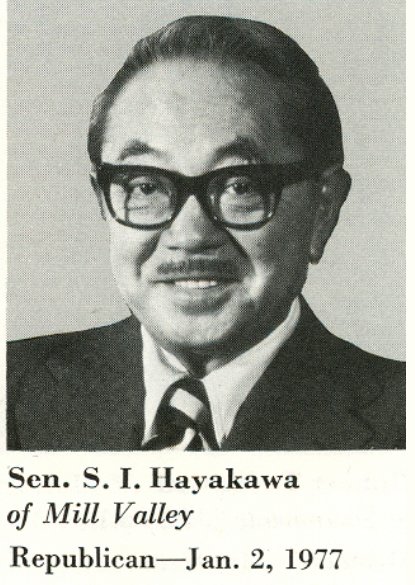

Lau v. Nichols (1974), from English-only policies to greater acceptance of and investment in bi- and multilingual education. However, there were still many who opposed this shift, even among non-white communities. For example, Senator Samuel I. Hayakawa (1906-1992) consistently opposed bilingual education. He even proposed

legislation in the early 1980s to make English the official language of the United States and to repeal the bilingual requirements of the Voting Rights Act extension of 1975, which mandates that language assistance be provided to voters if more than five percent of voting-age citizens are members of a language minority group and do not speak or understand English well enough to participate in the electoral process. He supported bilingual education to the extent that it helped students gain English proficiency more quickly and easily, but believed in achieving a society where everyone spoke the common language of English. Such debates and arguments around bilingual education and bilingualism continue to occur to this day.

Bibiliography:

- Bilingual Education Act of 1968: an amendment to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965

- Bi-/Multilingual: able to speak or use two (bi-) or more (multi-) languages with fluency

- Direct Action: the use of strikes, demonstrations, or other public forms of protest

- Discrepancy: a difference between two things that should be the same

- Fourteenth Amendment: grants citizenship and the rights of citizens to all persons “born or naturalized in the United States”

- Legislation: the preparation and enactment of laws

- National Origin: the nation where a person was born

- Proficient: being skilled or competent

- Remedies: solutions to a problem

- Supplemental: provided in addition to what is already available in order to enhance it

- Voluntary: not required, optional

- What did you learn from the text?

- What were the conditions that led to Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- How did the ruling of Lau v. Nichols (1974) shift the way English language learning was approached in the classroom?

- What were the effects of Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- What was Senator Samuel I. Hayakawa’s position?

Activity 1: Ideal Learning Environment

- Distribute sticky notes. Have students write down at least three characteristics of their ideal learning environment - one characteristic per sticky note.

- Pose the following questions to help students consider what makes up a learning environment:

- How would you like to be taught? (i.e., lecture, hands-on activities, reading, multimedia, virtual, etc.)

- What is your ideal classroom? What would it look, sound, and feel like?

- Who is in the ideal classroom with you?

- Have students talk to a partner and discuss how each characteristic listed on the sticky note would help them learn better. Also, have students note things that would clash with their own ideal environment.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How did it feel to design your ideal learning environment?

- How did it feel to know that some of your classmates’ ideal environments would clash with yours? What is the solution in this instance?

- What did you learn from this activity?

- Share the following statement: “This activity was meant to demonstrate how different students might have different needs and might learn better when different resources, strategies, and classroom set-ups are used. In this lesson, we’ll be learning about the experiences of English Language Learners in relation to the support they need to succeed in an English-dominant education system.”

Activity 2: Identifying Enduring Issues

- Have students read the text entitled, “English Language Education Policies in the United States.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If you have limited classroom time, have students complete the reading as a homework assignment the night before you implement this lesson.

- Facilitate a discussion of the text by asking the following questions:

- What did you learn from the text?

- What were the conditions that led to Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- How did the ruling of Lau v. Nichols (1974) shift the way English language learning was approached in the classroom?

- What were the effects of Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- What was Senator Samuel I. Hayakawa’s position?

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue.” (See Answer Key.)

- Tell students that enduring issues are issues that exist across time.

- Explain that an enduring issue is a challenge or problem that a society has faced and debated or discussed over time.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, give students examples of “enduring issues” such as strain on resources, threats to privacy, violations of human rights, disputes between social classes, anti-Blackness, disputes over land acquisitions, etc.

- Ask students to identify the enduring issue conveyed in the text and write that at the top in Part 1. Guide students toward the topics of: (1) English-only vs Bi-/Multilingualism; (2) Anti-immigrant sentiments; (3) Superiority of English language; (4) another similar theme.

- Model how to complete Part 2 of the worksheet entitled, “Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue.” Have students do the following:

- Identify four characteristics of the enduring issue in the left column.

- Write how each event interacts with each characteristic in the middle four columns.

- Identify and record information that helps to establish what has changed and what has remained the same over time in the fourth column.

|

Strategy: Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue Tool

The theme of continuity and change is a major concept in the study of history. Historians often organize their thinking about the past by examining what has changed (change) and what has stayed the same over time (continuity). They also examine the underlying reasons as well as the effects of changing or not changing.

For more on teaching Continuity and Change, see:

|

The Chinese Education Center Elementary School (now called the Edwin and Anita Lee Newcomer School) in San Francisco, CA is a school for Chinese-speaking, newly-arrived immigrant students with a year-long program to develop English skills.

Credit: “Chinese Education Center Elementary School” by TeacherLiT, via Wikimedia Commons (

CC BY-SA 3.0)

Activity 3: Lau v. Nichols (1974)

- Have students watch the following video: “SFUSD Bilingual Education Lau vs Nichols” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cXhQrJ37gFE

- NOTE TO TEACHER: There are a couple of concepts mentioned in the video that students may not be familiar with. Some background information is provided below:

- The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act abolished the National Origins Formula which restricted Asian immigrants and favored European immigrants. Instead, the 1965 Act established a preference system based on professional skills needed by the United States, and those who had a pre-existing family tie in the country. As a result, there was an increase of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Central and South America; many of whom had limited English skills. If needed, teach The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 - Civil Rights Movement Era”: https://asianamericanedu.org/immigration-and-nationality-act-of-1965.html

- Ethnic Studies is the result of the two longest student strikes in U.S. history. These strikes were led by youth of color forming the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) at San Francisco State College (now University) and University of California, Berkeley. If needed, teach The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “The Fight for Ethnic Studies”: https://asianamericanedu.org/ethnic-studies-the-fight-to-teach-our-stories.html

- Have students take notes while watching and complete the worksheet entitled, “Video Viewing Guide.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If short on time, have students complete the video-watching activity at home.

|

Strategy: Video Viewing Guides

Watching videos is an effective learning tool. But, teachers need to provide opportunities for students to interact with the videos versus passively watching them. Viewing guides enable students to transact with video content. Strategies should assume a “Watch-Think-Write” approach or a “See, Think, Wonder” approach.

For more on Video Viewing strategies, see:

|

- Review responses to the “Video Viewing Guide.” (Use Answer Key as notes.) Review each of the questions and monitor student responses for misunderstandings and clarify as needed:

- What did you hear?

- What did you see?

- What did you realize?

- What did you wonder?

- What are the central ideas of the video?

- What perspective is being presented?

- What is the purpose of the video?

- What biases are evident in the video?

- How does the perspective, purpose, and potential bias inform your understanding or interpretation of the information presented in the video?

- How will you apply the information and evidence from the video to your understanding on the enduring issue?

- Facilitate a discussion of the video by asking the following questions:

- What is the purpose of bilingual education, as defined by the video?

- What did the video reveal about Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- What challenges did recent immigrants face in San Francisco schools?

- What were the effects of Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

- What does this quote mean to you: “In the 30 years since the Lau decision, bilingual education programs continue to be controversial. Detractors, many of whom are educators, believe students will function better in mainstream classrooms. At times, bilingual education has been attacked by special interests who are trying to make a biased point about immigration policies.” (Video Clip: 4:12-4:36)

- How do the goals of bilingual education compare to the views of Senator Hayakawa on the education of English Language Learners?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: For your reference, the video lists the goals of bilingual education as improving students’ English proficiency, core curriculum in primary languages, and maintaining students’ cultural identity. Senator Hayakawa, on the other hand, only supported bilingual education to build English proficiency in a society where English is the official language.

- Have students retrieve the worksheet entitled, “Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue” which they had completed in the previous activity. Have students add information that they had learned from the video to it.

- Have students complete Part 3 of the worksheet entitled, “Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What is an example of a continuity for this enduring issue?

- What is an example of a change for this enduring issue?

- Was there greater continuity or change for this issue over the course of these events?

Activity 4: Quickwrite on Enduring Issues

- Have students complete a Quickwrite given this prompt: Why are the issues presented in this case enduring?

|

Strategy: Quickwrite

A Quickwrite is an instructional practice that allows students an opportunity to quickly respond to a question or prompt. It is often timed for 3-10 minutes. It provides teachers an assessment of what students know or think at that moment in time. It provides students an opportunity to freely write down their first thoughts. It can be used at any time in a lesson.

For more on Quickwrites, see:

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share what they wrote in their Quickwrites.

NOTE TO TEACHER: This lesson is optional. The purpose of this lesson is to connect the content to New York. If pressed for time, teachers can skip and go directly to Day 3. Or, teachers can assign relevant parts of this lesson as homework.

Activity 1: Sink or Swim

- Ask students: Have you ever heard the phrase, “sink or swim”?

- Explain that this means throwing someone who can’t swim into the pool and having them learn to swim by either sinking or swimming; in other words, it refers to a situation in which someone either must succeed by his or her own efforts or fail completely.

- Divide students into groups of three and have them share personal examples of when they had to sink or swim.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How did you feel when you were forced to learn or do something completely new to you without any support?

- What would have helped you learn better?

- How might English Language Learners feel in a classroom that is taught in English?

Activity 2: Aspira v. New York (1975)

- Share the following statement: “There was an important court case in New York, Aspira v. New York (1975). This case led to the ASPIRA Consent Decree which mandated transitional bilingual programs for Spanish-speaking students. Transitional bilingual programs are an approach to bilingual education; students first acquire fluency in their native language and then they acquire fluency in the second language. The goal is to transition students into English-only classrooms as quickly as possible.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Aspira means “to aspire” in Spanish. In 1961, a group of Puerto Rican educators and professionals created ASPIRA. They wanted to address the high dropout rate and low educational attainment of Puerto Rican students who were failing English-only classes. They started in New York and have grown into a national association.

- Play the video entitled, “A historical background of bilingual education”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tIppleeIjk

- Have students take notes while watching and complete the worksheet entitled, “Video Viewing Guide.” (Remind students of the modeling you provided in the previous lesson.)

|

Strategy: Video Viewing Guides

The Structured Historical Watching videos is an effective learning tool. But, teachers need to provide opportunities for students to interact with the videos versus passively watching them. Viewing guides enable students to transact with video content. Strategies should assume a “Watch-Think-Write” approach or a “See, Think, Wonder” approach.

For more on Video Viewing strategies, see:

|

- Review responses to the “Video Viewing Guide.” (Use Answer Key as notes.) Review each of the questions and monitor student responses for misunderstandings and clarify as needed:

- What did you hear?

- What did you see?

- What did you realize?

- What did you wonder?

- What are the central ideas of the video?

- What perspective is being presented?

- What is the purpose of the video?

- What biases are evident in the video?

- How does the perspective, purpose, and potential bias inform your understanding or interpretation of the information presented in the video?

- How will you apply the information and evidence from the video to your understanding on the enduring issue?

- Facilitate a discussion by asking students the following questions:

- What new ideas did you learn from the video?

- How did the video support what you have already learned?

- How did the video contradict what you have already learned?

- How is this case connected to Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

Activity 3: Additional Sources on Aspira v. New York

- Have students work as partners or small groups to research more about Aspira v. New York (1975).

- Direct students to find at least one relevant source which could be an article, video, etc. (Allow students to find any available sources via the internet.)

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Summarizing the GIST.”

- Direct students to read and summarize the source by completing the worksheet.

- Allow students an opportunity to share their responses.

|

Strategy: Summarizing the GIST

Gist means the substance or essence of a text. The purpose of summarizing the gist helps students identify main ideas which will increase the likelihood that they will comprehend and retain content. In addition, students learn to distinguish between important versus interesting ideas.

For more on GIST strategies, see:

|

Activity 4: Comparing Lau v. Nichols (1974) and Aspira v. New York (1975)

- Allow students an opportunity to share their research on additional source(s) about Aspira v. New York (1975) using the Summarizing the GIST worksheet.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How are Lau v. Nichols (1974) and Aspira v. New York (1975) connected?

- How are these two cases similar?

- How are these two cases different?

NOTE TO TEACHER: If pressed for time, just do the Introduction and Wrap-Up activity. Skip the other tasks or assign them for homework.

Activity 1: Speaking One’s Native Language

- Show the video entitled, “Asian Americans Try to Speak Their Native Language”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8IBfgUNpRsY

- Facilitate a discussion by asking students the following questions:

- What resonated with you the most?

- What is the point of the video?

- Why is valuing one’s native language important?

- What do you think about English-only policies? Who benefits from these policies? Who doesn’t?

- Why is bilingual education important? Who benefits? Who doesn’t?

Senator S.I. Hayakawa pushed English as the official language of the United States. He supported bilingual education only to the extent that it helped students learn English faster, but otherwise opposed it.

Credit: “1979 Hayakawa p9” by United States Congress, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Activity 2: Analyzing Primary and Secondary Sources

- Remind students of the difference between primary sources (firsthand accounts) and secondary sources (secondhand accounts; information created from primary sources). Explain that primary sources are credible as evidence but can be hard to comprehend; secondary sources show how primary sources relate to existing knowledge and offer explanations or interpretations that can help foster further understanding.

- Divide students into five groups and assign each group to one of the following sources:

- Group #1: Analyzing a Primary Source: "Lau v. Nichols (1974) Case Opinion"

- Group #2: Analyzing a Secondary Source: "Languages, Law, and San Francisco" by Charles Euchner

- Group #3: Analyzing a Primary Source: “English, By Law” by S.i. Hayakawa

- Group #4: Analyzing a Primary Source: “Sen. Hayakawa’s Speech”

- Group #5: Analyzing a Secondary Source: “Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Lau v. Nichols”

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Analyzing Primary and Secondary Sources” and review the instructions with students:

- Tell students to note the title, author, date, and source of the text in the top box.

- Tell students to record observations in the left column.

- Tell students to record questions in the right column.

- Tell students to annotate as they read:

- Tell students to highlight or underline important ideas.

- Tell students to circle confusing vocabulary and concepts.

- Tell students to complete the reflection questions at the end of the worksheet.

|

Strategy: Analyzing Sources

(Observe, Reflect, Question Strategy)

Primary and secondary sources can be complex texts. But, they are necessary for historical thinking. Both sources complement each other in order to help learners build convincing arguments. Teachers can help students by providing prompting questions as they read.

For more on analyzing sources, see:

|

- Allow students time to read their assigned texts.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “6-3-1 Strategy.”

- Have students use their annotated notes to complete the left column. Have them identify the top six most important understandings from the text.

- Have students work with a partner who read the same article. Have them complete the middle column. Have them share their six understandings with each other and from those understandings, create the top three understandings based on their combined understandings. Encourage them to combine sentences, to summarize, or to create new ideas or interpretations.

- Have students work with a partner who read a different article from them. Have them share their top three understandings and create one summary statement. Have them record their statement in the right column.

- Have students share their statements aloud.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking students the following questions:

- What do all the texts have in common?

- How do the texts differ?

- What more did you learn about the impacts of Lau v. Nichols (1974)?

|

Strategy: 6-3-1 Strategy

The 6-3-1 Strategy is adapted from the 5-3-1 strategy. As a summarizing tool, this strategy helps students distill information to its essence. It also promotes collaboration and conversation.

For more on the 6-3-1 Strategy, see:

|

The DeAvila School is one of several schools in San Francisco, CA with a Chinese language immersion program.

Credit: “Chinese Immersion School at DeAvila in San Francisco, California” by GeorgeLouis/BeenAroundaWhile, via Wikimedia Commons (

CC BY SA-3.0)

Activity 3: Understanding Historical Significance

- Share the following statement: “Everything that has ever happened is history. There is too much history to remember. As such, historians focus on significant events. Significant events are those that have resulted in great change over long periods of time for large numbers of people. Significance depends on one’s perspective and purpose. Significance can also be debated.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If students need help understanding this concept of significance, have them recall a significant event in their own lives and question them on why these events are significant and how they determined their significance.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Historical Significance Tool.”

- Explain the criteria for determining significance (left column) - tell students that these criteria are not definitions but guidelines for thinking historically:

- Importance: This measures the impact on the lives of those living at the time. Encourage students to empathize with the people in the past to more clearly assess their perspective and context.

- Profundity: This measures how deeply people were impacted. It doesn’t matter if the event was negative or positive.

- Quantity: This measures the number of people affected. Make sure students understand that quantity does not mean quality.

- Durability: This measures the impact of past events on subsequent events and the present. Make sure students understand that short-lived events can have great long-lasting effects.

- Relevance: This measures the significance of an event to the present.

- Tell students to refer to the texts read in this lesson as evidence of their thinking.

- Tell students to evaluate the criterion in the right column with a “yes” or “no.”

- Tell students to answer the question in Part 2: Was this event or case historically significant?

- Have students work with a partner to complete the worksheet.

|

Strategy: Historical Significance Tool

Significant events are those that have resulted in great change over long periods of time for large numbers of people. Significance depends on one’s perspective and purpose. The Historical Significance Tool helps students make an argument for whether a particular event is considered significant.

For more on the Historical Significance Strategy, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: As an optional activity, have students create an infographic about the history and impacts of Lau v. Nichols (1974). If students are not familiar with infographics, tell them that infographics are used to help communicate information (i.e., instructions, research findings, facts on a topic, etc. ). Infographics incorporate both text and graphics. They don’t usually have large chunks of text. The layout of the information helps readers better process information. Select some examples of infographics from the following website to show your students: https://piktochart.com/blog/infographic-examples-students.

Activity 4: Significance of Lau v. Nichols on Public Education

- Facilitate a discussion or have students write a response paper given these prompts: How and why is the Lau v. Nichols (1974) case significant to public education in the United States? How did it change education? How does it advance the civil rights of marginalized communities?

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Multilingual Education unit: Summarize this set of lessons by sharing this statement: “This lesson has mainly focused on how Asian Americans have won significant court cases that have greatly impacted bilingual education in the United States. The next lesson will focus on the first group of Asian immigrants who benefited from the changes in bilingual education: the Southeast Asian refugees who came to the United States as a result of the Vietnam War.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: In addition to Lau v. Nichols (1974), Asian Americans have made other significant contributions to public education. For example, Congressmember Patsy Mink spearheaded Title IX which prohibits discrimination based on gender in education programs. To learn more about Mink, teach The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “Women Advancing Equality: Patsy Mink” (https://asianamericanedu.org/women-advancing-equality-patsy-mink.html). In another example, Asian American university students in collaboration with Black American and Latinx American students fought for the teaching of ethnic studies in schools. To learn more, teach The Asian American Education Project’s “The Fight for Ethnic Studies” (https://asianamericanedu.org/ethnic-studies-the-fight-to-teach-our-stories.html).