Grade: 7-10Subject:

History, Social Science

Number of Lesson Days: 2

Throughout U.S. history, labor has been tightly tied to race. After the abolition of slavery, Black people continued to be relegated to low-wage jobs, and as demands for cheap labor grew, immigrant laborers were seen as the solution. In this two-day lesson, students will learn about three examples of cross-cultural solidarity between Asian Americans and other communities of color in their fight for fair wages and working conditions: Delano Grape Protest, I-Hotel Protest, and New York Taxi Workers Alliance Protest. On Day 1, students will analyze each of these protests by considering the economic, social, political, and cultural issues involved. On Day 2, students will conduct an image analysis of images of the three protests.

How did Asian American communities work with other communities of color to advocate for fair wages and working conditions?

Students will analyze photographs as primary sources in order to examine the collaboration between Asian Americans and other communities of color in their fight for labor rights.

Workers Find Strength in Numbers Essay:

Background:

Throughout U.S. history, labor has been tightly tied to race. The United States relied on the institution of slavery, with enslaved people providing the labor that spurred the nation’s economic growth and power since its earliest history. After the

abolition of slavery, Black people continued to be relegated to low-wage jobs with poor working conditions. As the United States expanded westward during the 19th century, demands for cheap labor grew and immigrant laborers were seen as the solution.

Essay:

Throughout U.S. history, labor-intensive and dangerous jobs have often been relegated to those with little power to find employment elsewhere, namely people of color and poor and uneducated whites. With the end of slavery, the United States filled demands for cheap labor with immigrant workers. These immigrants were subject to the existing

racial hierarchy in the United States. As such, they faced differential treatment in regards to pay, benefits, and working conditions. For example, non-white immigrants were treated worse than white immigrants, but white immigrants were treated more poorly than native-born whites. This tactic served to create divisions among workers to keep workers in competition with one another and to discourage them from working together to demand better treatment. These workers took on dangerous, low-paying jobs in mines, on the railroads, in

agricultural fields, and more. In many ways, immigrant laborers drove U.S. growth and expansion.

One such group of immigrant laborers were the Filipino men who began settling in California’s Central Valley in the 1900s. Filipino immigrants worked as field laborers filling a demand for more workers on California’s farms. Filipinos faced racial violence, housing discrimination,

anti-miscegenation laws, and language barriers due to existing anti-Asian racism. Immigration restrictions kept Filipina women from migrating easily to the United States and anti-miscegenation laws prevented Filipino men from marrying outside their race, and so many male Filipino farm workers remained single into their old age. These bachelor Filipinos are called

Manongs, a term of respect given to older men. As farmworkers, the Filipino men didn’t receive healthcare or

pensions, and faced long and back-breaking work hours, low wages, crowded living areas, and even non-functioning toilets.

In September 1965, Larry Itliong (1913-1977), a Filipino labor leader, began to organize farmworkers in Delano, California. Itliong was a co-founder of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) and dedicated to seeking justice for workers. In Delano, he met with Filipino workers and convinced them to initiate a strike against the grape growers to demand better wages, the right to form a union, and more. After the

strike began, Itliong and other Filipino leaders contacted Mexican farmworkers to join them in the strike to prevent the growers’ ability to use Mexican farmworkers to break the strike. Cesar Chavez (1927-1993) and Dolores Huerta (born 1930), members of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), took the request back to their members. One year later, AWOC and NFWA merged to become the United Farm Workers (UFW) and stood together in the strike.

The Delano Grape Strike lasted for five years, through which the farmworkers supported each other and their families. The strike inspired many people across the country and around the world. The farmworkers also organized a

boycott of grapes which even reached Europe. In July 1970, over thirty grape growers in Delano agreed to the demands to increase wages, contribute to union health plans, and control of toxic

pesticides to end the strike. This victory would not have been possible without Filipinos and Mexicans coming together and building their bargaining power to win the demands they made. Furthermore, this effort also led to the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, which provided collective

bargaining rights for farmworkers across the state.

Another example of organizing with and for Manongs is the International Hotel battle of the 1960s and 1970s in San Francisco, California. Known as the I-Hotel, the single room occupancy hotel served as home for many Manongs, including retired migrant farmworkers, merchant marines, and service industry workers. It was one of the few buildings where the Manongs, who did not receive any retirement benefits, could afford to live; and if the hotel was demolished, they would be losing their homes and community. In 1968, the building’s owner issued

eviction notices to carry out plans to demolish the hotel to build a parking garage in its place. The community immediately pushed back, and in response to that pressure, the owners agreed to lease the building to the United Filipino Association for three years, temporarily saving the hotel from demolition.

In 1973, the I-Hotel was sold to another corporation, and the new owner issued eviction notices the next year. For three years, tenants and their supporters tried to fight the eviction orders. College students, activists, union members, and church members (from diverse racial groups) joined the struggle in support of the elders living in the I-Hotel. The fight for the I-Hotel grew to represent

displacement pressures that were impacting other

vulnerable communities. On the night of August 4, 1977, over three thousand multi-racial protesters joined to create a human barricade outside the I-Hotel in order to prevent the eviction of the fifty-five remaining, mostly elderly, tenants. However, police made their way through the protestors with their batons and used sledgehammers to break down the doors to remove tenants. In 1981, the hotel was demolished.

Despite the loss of the hotel, the nine-year fight and powerful protest on the night of the final eviction had a lasting impact. The determination of the remaining I-Hotel

advocates led to the creation of the International Hotel Senior Housing with one hundred low-income housing units, and the I-Hotel Manilatown Center on the site of the old I-Hotel. Additionally, the struggle brought awareness to the need for neighborhood preservation and affordable housing for low-income people. Still, these small victories came too late for the majority of the evicted I-Hotel tenants, most of whom had passed away by the time the new hotel was completed. Of the original tenants, only a couple were able to move into the new I-Hotel.

Another impressive example of multiracial labor struggle took place in New York City in 2021 through the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA). Formed in 1998, the NYTWA quickly grew its membership to include drivers of different races, ethnicities, and backgrounds, creating a multiethnic membership representative of New York City’s drivers. About 94 percent of taxi drivers are immigrants, and the majority of immigrant drivers are South Asian, followed by immigrants from the Caribbean. Accordingly, the NYTWA membership is made up heavily of Black and

Brown drivers. By building strong relationships with drivers and centering their needs and demands, the NYTWA steadily grew its base to include over 21,000 members across taxi, app-based, and other professional drivers in preparation for its next strike.

In September 2021, NYTWA channeled three years of prior organizing for

debt relief for drivers into a 24/7

encampment outside of City Hall. New York City’s policy for leasing taxicab permits relied on

predatory loans that placed drivers deep in debt. Drivers had been unsuccessfully requesting debt relief and aid for years. By 2021, the average debt of leasing drivers was over $550,000, and nine drivers had committed suicide due to their debt over the last few years. Drivers had decided that it was time to

escalate their demand for debt relief and set up camp outside City Hall. Drivers, family members, elected officials, and community members advocated day and night for debt relief. After one month, a group of more than twelve drivers announced a

hunger strike, again escalating their strategy to persuade the mayor to include debt relief in the city budget. Some elected officials and community members joined the hunger strike in solidarity; a few were even arrested in an act of

civil disobedience to bring awareness to the strike through their elevated position.

The dedication of the drivers and their supporters eventually paid off. After six weeks of non-stop

mobilization and a fifteen-day hunger strike, the city agreed to restructure the loans to bring down the total driver debt and limit the maximum monthly debt payments. This victory was built upon the very first NYTWA strike in 1998 and the three years of advocacy and planning leading up to the 2021 strike, resulting in a huge win for a predominantly Black and Brown immigrant workforce.

Each of aforementioned struggles relied on the solidarity between workers and the support and solidarity of those with more power to be able to enact change. They had strength in numbers. They also did not waste time fighting each other. Instead, they joined forces to change an unfair system.If there had been any racial, ethnic, or other divisions, these campaigns would have had very different outcomes. Cross-cultural solidarity was key to helping champion workers and their needs.

Bibiliography:

Heer, Prabhneek. “Tactics Used to Promote Civic Participation and Action in APIDA Communities.” National Council for the Social Sciences, Social Education, Volume 86, Number 2, March/April 2022, pp. 95-103(9).

- Abolition: ending of

- Advocates: one who defends or maintains a cause or proposal

- Agricultural: related to farming

- Anti-miscegenation: prohibition of marriage between people of different races

- Boycott: to ban as an act of protest

- Brown: a term used as an identifier for South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Latinx people

- Civil Disobedience: refusal to obey governmental demands or commands especially as a non-violent and usually collective means of forcing concessions

- Collective Bargaining: negotiation between an employer and labor union usually on wages, hours, and working conditions

- Debt relief: strategies aimed at making debt easier to pay

- Displacement: the act or process of forcing people to leave from their home or homeland

- Encampment: camps set up by activists planning to stay for an extended period of time

- Escalate: to increase in extent, volume, number, amount, intensity, or scope

- Eviction: removal of a tenant from rental property by the landlord

- Hunger strike: non-violent tactic where participants fast as an act of political protest

- Mobilization: the act of putting things into motion

- Pension: fixed sum paid regularly to a person, usually related to retirement

- Racial hierarchy: a system based on the belief that some racial groups are superior to others

- Pesticides: substance used to kill insects harmful to plants

- Predatory: seeking to exploit or oppress others

- Strike: to stop and disrupt work in order to force an employer to comply with demands

- Vulnerable: at risk of being targeted

- In what ways did the United States rely on the labor of people of color?

- In what ways were workers treated differently and why?

- Who were the Manongs and what was their plight?

- What is the history and significance of the Delano Grape Strike? How and why did Filipino and Mexican immigrant farmworkers work together to fight for labor rights?

- What is the history and significance of the International Hotel protest? How and why did communities of color work together? How did this protest address labor and/or human rights?

- What is the history and significance of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance protest? How and why did communities of color work together to fight for labor rights?

- Why was cross-cultural solidarity key to the success of these protests?

- What would have happened if the communities of color did not stand in solidarity?

Union workers urged the boycott of lettuce, grapes, and wine grown in California by growers who signed contracts with the Teamsters.

Credit: “Union Pickets the Jewel Food Store” by photographer Paul Sequeira. DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972 - 1977. NAID:

551939

Activity 1: Introduction to Labor Rights

- Ask students the following question to access their prior knowledge:

- When you get a job, what are some of your expectations in regard to wages, benefits, and working conditions?

- What are some concerns or issues around labor in the United States?

- What do you know about labor unions?

- What rights do workers have or should have in the United States?

- Why did certain groups of people have to fight for their rights as workers?

- Share the following statement with students: “Asian Americans in solidarity with other communities of color have made significant contributions to the history of labor rights in the United States.”

Activity 2: Workers Find Strength in Numbers

United Farmworkers of America mural in Modesto, California.

Credit: “United Farm Workers of America mural - September 2023” by Sarah Stierch Missvain via

Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Activity 3: Solidarity for Labor Rights

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Solidarity for Labor Rights (ESP+C Chart).” Tell students they will be comparing and contrasting the Delano Grape Protest, I-Hotel Protest, and NYTWA Protest.

- Have students complete the chart by referring to the text and video:

- Have students record who was involved in each of the protests.

- Have students record the issues in each of the protests.

- Have students record the tactics used in each of the protests.

- Have students record the results of each of the protests.

- Have students record the economic issues involved in each of the protests. Explain that the “Economic” section addresses income, wealth, goods, and services. In this section, have students think about issues related to profit, wages, etc.

- Have students record the social issues involved in each of the protests. Explain that the “Social” section addresses human society. In this section, have students think about issues related to stereotyping, social status, social mobility, solidarity, etc.

- Have students record the political issues involved in each of the protests. Explain that the “Political” section addresses anything related to the government. In this section, have students think about issues related to laws, policies, etc.

- Have students record the cultural issues involved in each of the protests. Explain that the “Cultural’ section addresses the ways of life of groups. In this section, have students think about issues related to issues such as language, race, ethnicity, customs, behaviors, etc.

- Walk around as students are working and be available to answer any questions or clarify misunderstandings for students. (See Answer Key: Solidarity for Labor Rights (ESP+C Chart))

|

Strategy: ESP+C Chart)

ESP+C stands for Economic, Social, Political, and Cultural. These four broad categories can be used to organize important historical changes. Analyzing events using these four categories allows students to create a general narrative of past events. In addition, this tool helps students avoid evaluating past events by today’s values.

For more on the ESP+C Chart, see:

|

Activity 4: Reflecting on Solidarity for Labor Rights

- Have students complete a Quickwrite given these prompts: How have Asian Americans used solidarity with other communities of color as a strategy to gain labor rights? What are the effects of their solidarity? What significant contributions to the history of labor rights in the United States did Asian Americans and other communities of color make?

|

Strategy: Quickwrite

A Quickwrite is an instructional practice that allows students an opportunity to quickly respond to a question or prompt. It is often timed for 3-10 minutes. It provides teachers an assessment of what students know or think at that moment in time. It provides students an opportunity to freely write down their first thoughts. It can be used at any time in a lesson.

For more on Quickwrites, see:

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share what they wrote in their Quickwrites.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: As an optional activity, have students research each protest further. Direct them to learn more about the challenges the communities faced. Working in solidarity across various racial and cultural groups can be difficult. For example, in the Delano Grape protest, Filipino and Mexican farmworkers had to overcome language and cultural barriers.

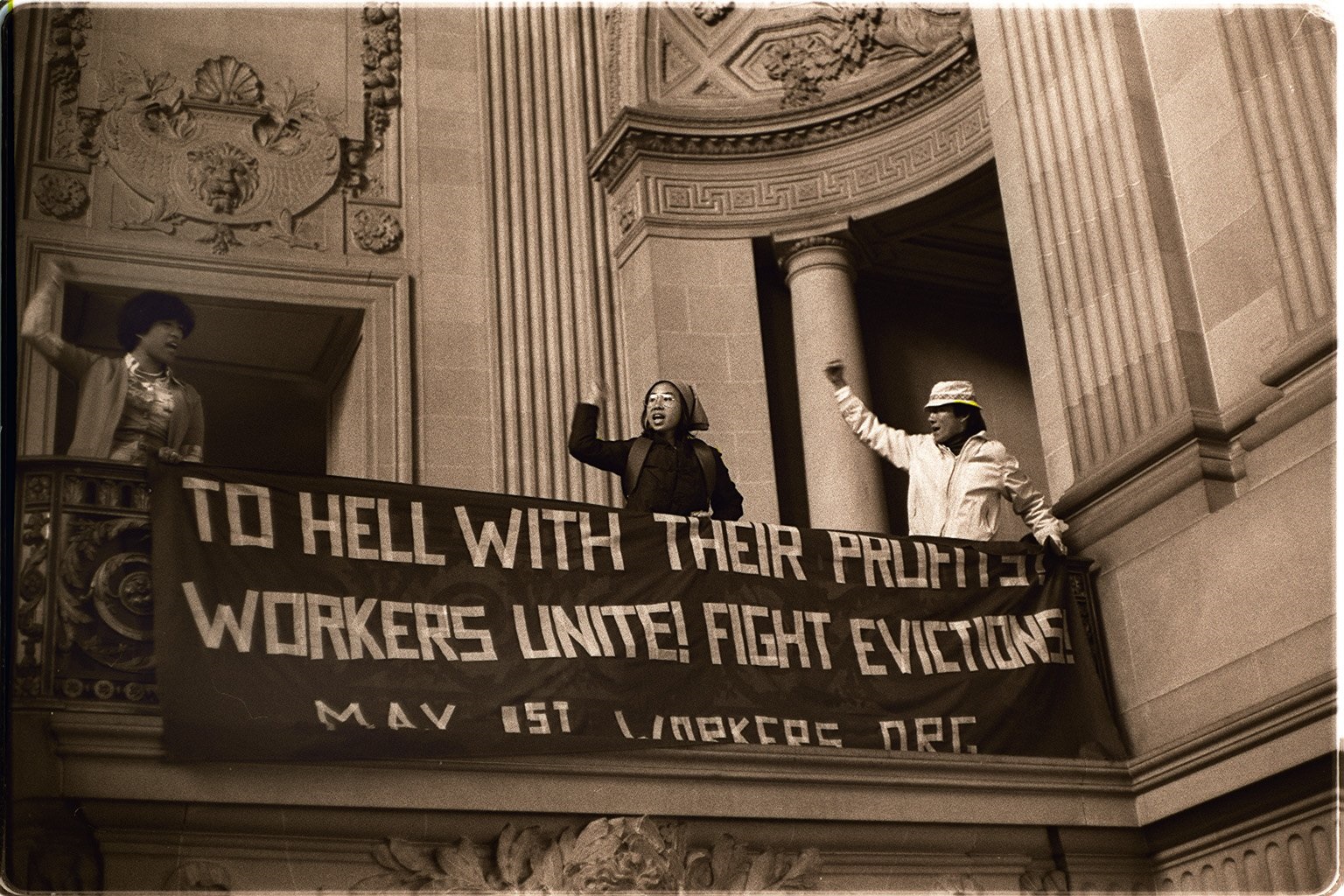

Protesters in support of the International Hotel tenants display a banner that reads “To hell with their profits. Workers unite! Fight evictions!”

Activity 1: Images as Primary Sources

- Tell students that images (i.e., photographs and artwork) are primary sources in that they serve as firsthand accounts.

- Ask students the following questions:

- Why are photographs important as historical records?

- How are photographs essential for studying marginalized groups?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Ensure students understand that photographs provide glimpses into lives past, long-ago events, and forgotten places. They can serve as memory aids, surrogates for direct observation, and historical documents. They are powerful tools for telling stories and chronicling events. They also have been essential in including the stories of people who often get left out of written history. There has been a tendency for history only to focus on major political figures (i.e., great white men), while ignoring other groups. Photographs allow us to have a deeper understanding of how “real” and “ordinary” people lived in particular time periods and how they molded the society. Photographs provide a glimpse into sections of society that have not been explored or examined. The lives of the common people are often overshadowed by the famous. Photographs add to the historical discourse. (Note that photography wasn’t invented until 1839.)

- Ask students:

- In what ways do you chronicle your life via photographs?

- If historians in the future wanted to study the period in time that we are currently living in, how might your social media feeds be an important source of information?

Demonstrators link arms in front of the International Hotel on 848 Kearny and Jackson Streets in San Francisco on August, 4, 1977.

Activity 2: Image Analysis

- Distribute three copies of the worksheet entitled, “Image Analysis Tool.”

- Review the instructions:

- Have students print a small thumbnail of the image and attach it to the top of the page. Or, students can attach a separate page. Or, students can just refer to the source.

- Have students record the source at the top.

- Have students complete Step One by answering the following questions:

- What do you see? What’s in the image?

- What information is provided in the title, citations, and context?

- When was the image taken?

- Have students complete Step Two by answering the following questions:

- What do you think is happening in the image?

- What connections can you make to a historical moment? What was happening at the time the image was taken?

- What can the source information tell you about the image?

- Have students complete Step Three by answer the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the image? Why was the photograph taken? (Record answer in the “Purpose” column.)

- What is the perspective or bias presented in the image? Who or what is being shown versus who or what is not being shown? (Record answer in the “Perspective & Bias” column.)

- How reliable is the image? Can we trust the source? Is it a real photograph? Has it been altered in any way? What are the limitations of the image? What is around the image that is not captured in the frame? (Record answer in the “Reliability & Limitations” column.)

- Have students complete Step Four by answering the following questions:

- How does this image show Asian Asian American communities working with other communities of color to advocate for fair wages and working conditions?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If needed, model how to complete the worksheet with the students by using a photograph from the internet. This is an example of a photograph you can use for modeling: https://ufw.org/larryitliongday2021/

|

Strategy: Image Analysis Tool

Analyzing images is an important skill as images and visuals are all around us. The Image Analysis tool assists students in identifying and analyzing the meanings of the images. By critically analyzing images, students enhance their observational, interpretative, and critical thinking skills.

For more on the Image Analysis Tool, see:

|

Activity 3: Corroborating Images: Delano Grape Protest, I-Hotel Protest, and NYTWA Protest

- Direct students to search the internet and select one photograph to study from each of the three protests mentioned in this lesson.

- Worksheet 1: Delano Grape Protest

- Possible Source: “¡VIVA LA HUELGA!: ARTWORK OF THE UNITED FARM WORKERS”: http://amadeusmag.com/blog/viva-la-huelga-art-united-farm-workers/ (Note this is artwork which is also a primary source.)

- Worksheet 2: I-Hotel Protest

- Possible Source: “The Battle for the International Hotel”: https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Battle_for_the_International_Hotel

- Worksheet 3: NYTWA Protest

- Possible Source: “The NYC taxi drivers’ hunger strike, in photos”: https://scienceline.org/2022/02/nyc-taxi-drivers-hunger-strike-photos/

- Have students complete the worksheets.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Corroboration Tool (Adapted).” Direct students to compare and contrast the photographs.

- Tell students that it’s important to corroborate sources so that we can make reliable and accurate conclusions.

- Have students complete the worksheet entitled, “Corroboration Tool (Adapted).”

- Identify elements of corroboration between the images. (On what point or facts do the images agree?)

- Identify elements of contradiction between the images. (On what points or facts do the images disagree?)

- Which image is more reliable? How so?

- What do all the images suggest about cross-cultural solidarity?

|

Strategy: Corroboration Tool

Corroboration is the ability to compare multiple pieces of information or sources in order to identify similarities and/or patterns. Finding corroboration between sources strengthens conclusions, especially when making historical arguments.

|

- Allow students an opportunity to share their responses to the last question of the “Corroboration Tool (Adapted)” worksheet: What do all the images suggest about cross-cultural solidarity?

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Cross-Cultural Solidarity unit: Summarize this set of lessons by sharing this statement: “We learned about three examples of cross-cultural solidarity between Asian Americans and other communities of color in their fight for fair wages and working conditions. In the next lesson, we will learn about how Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders joined forces with other communities of color to fight for land rights.”