Grade: 7-10Subject:

History, Social Science

Number of Lesson Days: 2

Within the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community, the issue of land rights impacts different ethnic groups differently. For Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, the issue of land rights centers the displacement of native people from their lands. For Asian Americans who migrated to the United States or who were born in the United States, land rights have historically centered access to land ownership. In this two-day lesson, students will learn about issues related to land rights and better analyze the motivations behind the resistance and solidarity of AAPI communities and other communities of color. On Day 1, students will focus on the history of Punjabi immigrants in California’s Imperial Valley. On Day 2, students will focus on the experiences of Native Hawaiians after colonization.

In what ways were Asian American and Pacific Islander communities denied access to land and property, and how did they work together with other communities of color to resist such discriminatory and/or imperialistic practices and policies?

Students will examine the enduring issue of land rights in order to better analyze the motivations behind the resistance and solidarity of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities and other communities of color.

Land Access and Exclusion Essay

Background:

Within the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, the issue of land rights impacts different ethnic groups differently. For Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, the issue of land rights centers the displacement of native people from their lands. For Asian Americans who migrated to the United States or who were born in the United States, land rights have historically centered access to land ownership. These differences are important to acknowledge because they not only illustrate the diversity of experiences within the AAPI community, but also affect the lived realities, struggles, and priorities of different AAPI communities.

Essay:

Access to and ownership of land has been fundamental to the formation of the United States as we know it today. From the colonial era to post-independence expansion, the allure of land ownership both drove immigrants to the United States and encouraged the expansion of the country through the taking of Native American lands. Land ownership and profiting from land became a way to build wealth and power. For example, after the United States declared its independence, voting rights were decided at the state level and many states only allowed white, property-owning men to vote. These requirements stayed in place until the early 1800s when owning property was no longer a requirement. This is just one example of the value of land in U.S. history. Whether through broken treaties, segregation, or exclusionary laws, the United States has historically tried to keep land out of the hands of non-white people.

Asian immigrants to the United States faced land discrimination in two key ways. First, Asian immigrants, like Black people and other people of color, were forced to live in

segregated neighborhoods. While some communities self-segregated to create strong

ethnic enclaves, many were forced into segregated neighborhoods either by law or in practice through exclusion, threats, violence, and discrimination by residents who wanted to keep their neighborhoods white. Second, as anti-Asian sentiments grew starting in the late 1800s, many states began to find ways to exclude Asians from the ability to own land. Some states explicitly banned Asians – or certain ethnic groups, such as the Chinese and Japanese – from owning land. Others banned the ownership of land by non-citizens, which specifically targeted Asian immigrants who were not eligible for citizenship through

naturalization until the 1940s. These laws became known as “alien land laws.”

Alien land laws were a coordinated effort to prevent Asian immigrants, most of whom had arrived in the United States as laborers, from permanently settling in the country. Depriving them of the ability to own land – for homes or for business – was one way to encourage them to return to their native countries. However, Asian immigrants found various ways to work around these laws. In some cases, they were able to have sympathetic white neighbors or friends purchase property for them. More often though, these immigrants started families and bought land under the names of their U.S.-born children. As U.S. citizens, these children were not impacted by the alien land laws and could own land.

Yet, even with this

loophole to the discriminatory alien land laws, there were restrictions placed on who these immigrants could marry.

Anti-miscegenation laws made it a crime for people of different races to engage in intimate relationships, especially marriage. The main purpose of these laws was to prevent whites and non-whites from marrying and having children. Additionally, restrictive immigration policies prevented Asian women from immigrating to the United States.

In the Imperial Valley of California, these policies led to the emergence of a unique

Punjabi-Mexican community. A large number of Punjabi immigrants in California worked on farms, putting their

agricultural skills from India to use. As a result, they regularly interacted with Mexican men and women who also worked in the California agricultural industry. Starting in the early 1900s, many of these Punjabi men decided to marry the Mexican women working in the Imperial Valley farms, starting families based on the accessibility of the women and their cultural similarities. Records show that over 350 Punjabi-Mexican marriages occurred across California in the early to mid-1900s.

These marriages, which were motivated by historical necessity, were made possible not only by the willingness of each person to accept the other’s culture, but also by the ignorance of the wider society. While anti-miscegenation laws prevented Asians from marrying outside their race, to most people, Punjabis and Mexicans were both simply considered “Brown.” As a result, their marriages were easily accepted and were not questioned. The community that emerged out of these unions was distinctly Punjabi-Mexican. The Mexican wives learned to cook Indian food alongside traditional Mexican foods. They were involved in the local

gurdwaras, and many families had strong ties with other Punjabi-Mexican families too.

In 1946, the Luce-Celler Bill was passed, allowing a certain number of Filipinos and Indians to immigrate to the United States. In addition, for the first time, it allowed these immigrants to naturalize as U.S. citizens. Because of this law, the Punjabi-Mexican community was significantly affected. Now that there were more opportunities for Indian men to marry Indian women, they often chose to do so. The newly immigrated Indian women often looked down upon the Mexican women who had married Punjabi men. Despite the gradual disappearance of this community, their existence is a historically significant example of how early Asian immigrants resisted racist land policies and practiced cross-cultural solidarity.

While Asian immigrants in the continental United States faced barriers to accessing and owning land, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have had to deal with the United States encroaching upon and taking their land for private or government use. In many ways, their experiences are similar to those of the

indigenous Native American communities, whose lands (upon which we currently reside) were taken away by the U.S government.

In Hawaii

ʻi, American economic and military interests in the islands led to its eventual colonization and statehood after a U.S.-backed coup overthrew the Hawaiian monarch in 1893. In 1848, the king of the Hawaiian Kingdom had enacted land distribution that opened land ownership to non-native Hawaiians, such as the powerful American businessmen on the islands looking to profit from sugar

plantations. By the end of the century, the majority of land was owned by American sugar plantation owners.

As a result of the plantation economy and U.S. military interests in Hawaiiʻi, a small number of corporations, individuals, and governments owned most of the land on the islands. As of 2021, there are eleven military bases across Hawaiiʻi, covering a total of five percent of the islands’ land. These military bases along with extensive tourism have negatively impacted the Hawaiian islands by increasing pollution, killing natural habitats, causing water shortages, and more.

Much of this land was taken by the U.S. government after the overthrow of the monarchy by the new government which was established by American businessmen. Native Hawaiians had no input in this decision. Likewise, the State of Hawaii

ʻi (which is an entity of the U.S. government, not to be confused with the Kingdom of Hawaii

ʻi) holds a large amount of land, some of which it leases out to other corporations or institutions. One such example is Mauna Kea, a volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii

ʻi. It is one of the world’s most remote places and a

sacred site for Native Hawaiians. In 1968, the state leased over eleven thousand acres of land on Mauna Kea to the University of Hawaii

ʻi for scientific purposes and gave the university permission to

sublease the land to contractors to build

observatories on the volcano’s peak. Since then, thirteen telescopes have been built on Mauna Kea, considered one of the best places in the world to study astronomy.

In 2014, a sublease was granted to add another, much larger telescope – the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT) – to Mauna Kea. The telescope would be one of the world’s largest. Scientists were very excited about the project. However, many people, including many Native Hawaiians, were not. They argued that adding yet another, larger telescope to the already crowded mountain would damage it. Additionally, as one of the most sacred sites for Native Hawaiians, Mauna Kea was not meant to be utilized in this way by humans based on indigenous traditions.

The project’s construction was heavily opposed by land protectors in Hawai'i. On July 15, 2019, when construction crews were called in to start work, the kiaiʻi – or protectors – created a blockade at the only access road to the summit, sitting in peaceful protest against the construction. After two days, the governor of Hawaiiʻi declared a state of emergency, dispatching police to the scene to arrest the protectors. Thirty-eight of the protectors, many elders in their 70s and 80s, were arrested and the images and videos of the arrests led to a massive influx of support from all over the world.

Kiai

ʻi continued to camp at the parking lot of the access road for almost nine months, keeping watch for TMT construction crews. The camp had between thirty and three thousand

visitors on any given day. Protectors and visitors took care of each other at the camp. They cooked together, hosted locals and musicians from neighboring islands, created a “university” centering Native Hawaiian science and practices, and more. The camp also hosted relatives from and flew the flags of other Indigenous movements, including Guam, Northern Marianas Islands, Standing Rock, Cherokee, Navajo, Palestine, Tibet, Taiwan, West Papua, and Aotearoa. The protectors used social media to share their struggles, to build solidarity, and to communicate directly with supporters. Social media was an effective way to share calls to action that would support the Protect Mauna Kea effort. (Many communities of color and

allies joined the cause.)

In June 2022, as a result of the massive and sustained opposition to the TMT project, a state law was passed to create the Mauna Kea Stewardship and Oversight Authority, to whom authority of the mountain would be transferred. The eleven-member group would include representatives from the observatories, university, and community, including two seats for Native Hawaiians. The group will co-

administer the mounting with the University of Hawaii

ʻi in 2023 and take over fully in 2028. Native Hawaiians have tried to have their voices heard and included in matters related to Mauna Kea for years, and some land protectors see the bill as an important step toward regaining some control over the sacred site.

The struggle to protect Mauna Kea became a symbol of the historical inequities and land seizures from Native Hawaiians that occurred as a result of U.S. interests, and more broadly came to represent the importance of Indigenous control over their

ancestral lands. The Protect Mauna Kea campaign is similar to the indigenous land issues on the U.S. mainland, such as the NoDAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) campaign launched by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to fight the construction of an oil pipeline that the tribe says would harm sacred sites and drinking water. Just as water protectors from Standing Rock joined the camp at Mauna Kea in solidarity, Native Hawaiians – several of whom were active in protesting the TMT – traveled to North Dakota in 2016 to show their solidarity and support as well. In fact, people of all backgrounds joined the Sioux in encampments at the construction site, marches, fundraising, and more to sustain their struggle for environmental, racial, and economic justice.

For a nation that was built on land taken from indigenous peoples – through massacres, broken treaties, and forced removal – the issue of land rights is inherently tied to the white supremacy upon which the United States was founded. White supremacy drove the

genocide and displacement of indigenous people and motivated the banning of Asian immigrant land ownership. As a result, addressing these issues requires solidarity among victims and targets of white supremacy, who can build greater power when they support each other.

Bibiliography:

- Administer: to manage or supervise the execution, use, or conduct of

- Agricultural: related to farming

- Allies: people from privileged communities who support communities of color

- Ancestral: relating to members of your family from the past

- Anti-miscegenation: prohibition of marriage between people of different races

- Coup: a sudden decisive exercise of force; the overthrow of an existing government by a small group

- Ethnic Enclave: providing a space for individuals who share the same ethnic identity to create potentially beneficial relations

- Genocide: the deliberate killing of a large number of people from a particular nation or ethnic group with the aim of destroying that nation or group

- Gurdwara: a Sikh place of worship

- Indigenous: of or relating to the earliest known inhabitants of a place, especially a colonized place

- Loophole: an absence or something vague in a rule or law that allows people to get around it or avoid punishment

- Naturalization: the course of action taken to become a citizen of a country other than where one was born

- Observatory: a building or place equipped for observation of natural phenomena (as in astronomy)

- Plantation: a large farm or estate where cash crops are cultivated, usually specializing in one crop

- Punjabi: an ethnic group from North India and Pakistan

- Sacred: holy; entitled to reverence and respect

- Segregated: separated by race

- Sublease: a lease by a tenant to another person or group

- Visitors: supporters of the cause; non-Hawaiians are referred to as residents, guests, or visitors

- How does the issue of land rights impact Asian Americans versus Pacific Islanders? What are the similarities between the two groups? What are the differences?

- In what ways are land rights important to full participation in U.S. society? How do land rights build privilege? Who has access and who doesn’t?

- In what ways were Asian immigrants to the United States denied land rights? What did they do about it?

- What were the impacts of the anti-miscegenation laws and how were they connected to land rights?

- What were the origins and effects of the Punjabi-Mexican community in the Imperial Valley? How are the Punjabi-Mexican marriages an example of cross-cultural solidarity? How was this community affected by the Luce-Celler Bill?

- How are the experiences of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders similar to and different from Native Americans?

- How and why did the U.S. government occupy lands in Hawaiiʻi? What were the impacts of the U.S. presence in Hawaiiʻi?

- What is the controversy related to the Thirty-Meter Telescope at Mauna Kea? How did Native Hawaiians resist? How did other communities of color support them?

- How was the Protect Mauna Kea campaign similar to the No Dakota Access Pipeline campaign? How and why did the two communities support each other?

- Why is it important for communities of color to build solidarity when addressing issues of inequities?

Activity 1: Can a Person Own Land?

- Ask students a “Big Question”: Can a person own land?

- Write the question and display for all to see.

- Have students silently think about the question. Encourage them to jot down their thoughts and ideas.

- Engage students in a discussion. Tell students that there are no right or wrong answers and that everyone’s opinions should be valued but that there is room for change and argumentation.

|

Strategy: Big Question

Big Questions engage students. In general, questions generate more conversation and inspiration than statements. Big Questions do not necessarily have one correct answer (or any answers). They serve as a springboard for ideas and opinions. They spark further learning and research. As a classroom tool, they are useful for building anticipation about what will be taught in a lesson.

|

- Ask students a follow-up question: How does your positionality influence your thinking?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Push students to think about how the issue of land ownership could mean different things to different people. For example, have them consider the points of view from indigenous peoples whose lands have been taken away from them, from landowners who benefit from land ownership, from communities of color who are denied land ownership, etc. You could even discuss it at a more personal level and focus on the points of view of people in their own communities and families.

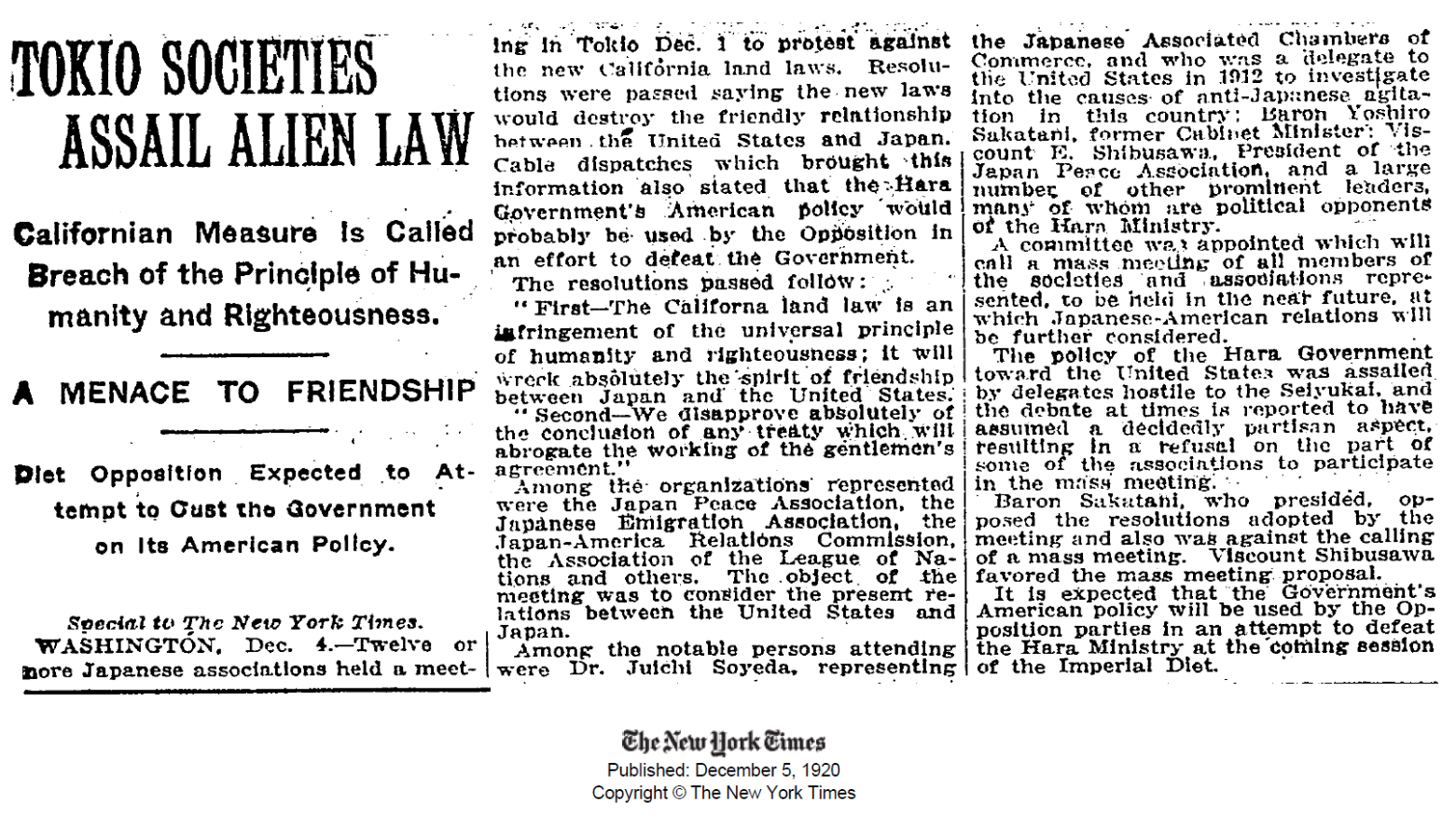

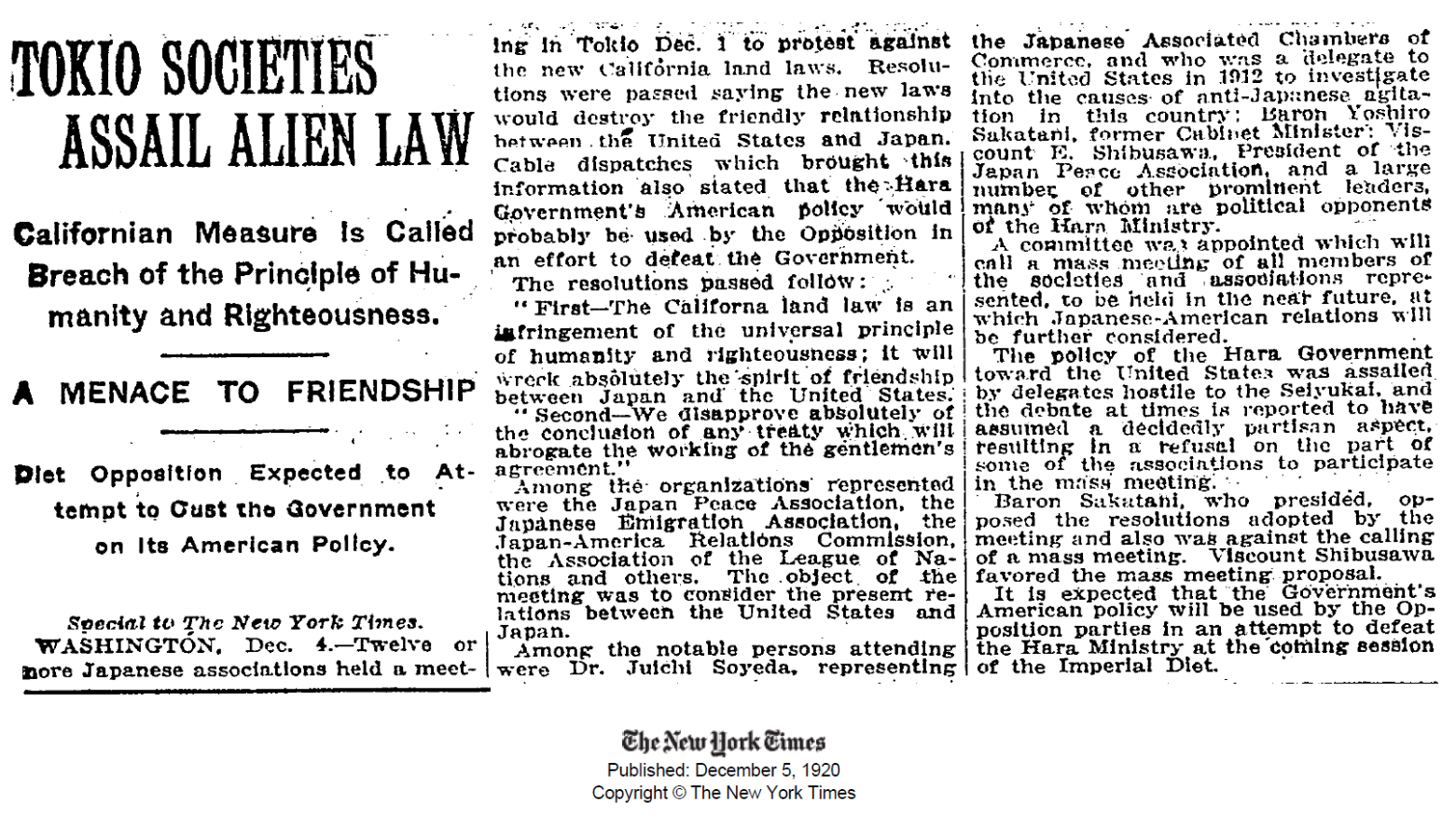

An article in The New York Times reporting on alien land laws in California. These laws deprived many Asian immigrants from owning land.

Credit: “Tokio Societies Assail Alien Law in the New York Times on December 5, 1920.”

CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED via Wikimedia Commons.

Activity 2: Land Access and Exclusion

- Distribute the text entitled, “Land Access and Exclusion.”

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Cornell Notes.”

- Direct students to read the text and complete the “Cornell Notes” worksheet as they read. Model how to closely read and complete the worksheet, if needed.

- Have students write the source information in the top row. Tell them to record the title, author, and date of publication.

- Have students record notes as they read in the right column. Tell them to define any unknown words, write down important key phrases, etc. Encourage students to paraphrase, use abbreviations, use symbols, etc. Encourage students to also take notes on the actual text by underlining important ideas and circling any confusions. Encourage them to write notes in the margins as well.

- Have students complete the left column after they are done reading. Tell them to look for patterns in their notes (in the right column) and write down main ideas. Also, tell them to write down their questions in the left column.

- Have students complete the last row after they have finished the rest of the worksheet. Tell them to summarize their reading by using their notes.

|

Strategy: Cornell Notes

Cornell Note-Taking System is an effective and popular note-taking strategy. The left column serves as a cue column; it is completed after reading. The right column is for notes and the bottom row is for summarization. Together, this system engages students in active reading and helps them organize their thinking.

For more on Cornell Notes, see:

|

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Feel free to use any note-taking strategy. The key is to give students an opportunity to practice note-taking and organizing their thinking.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time is limited, have students read the reading and complete the worksheet the night before.

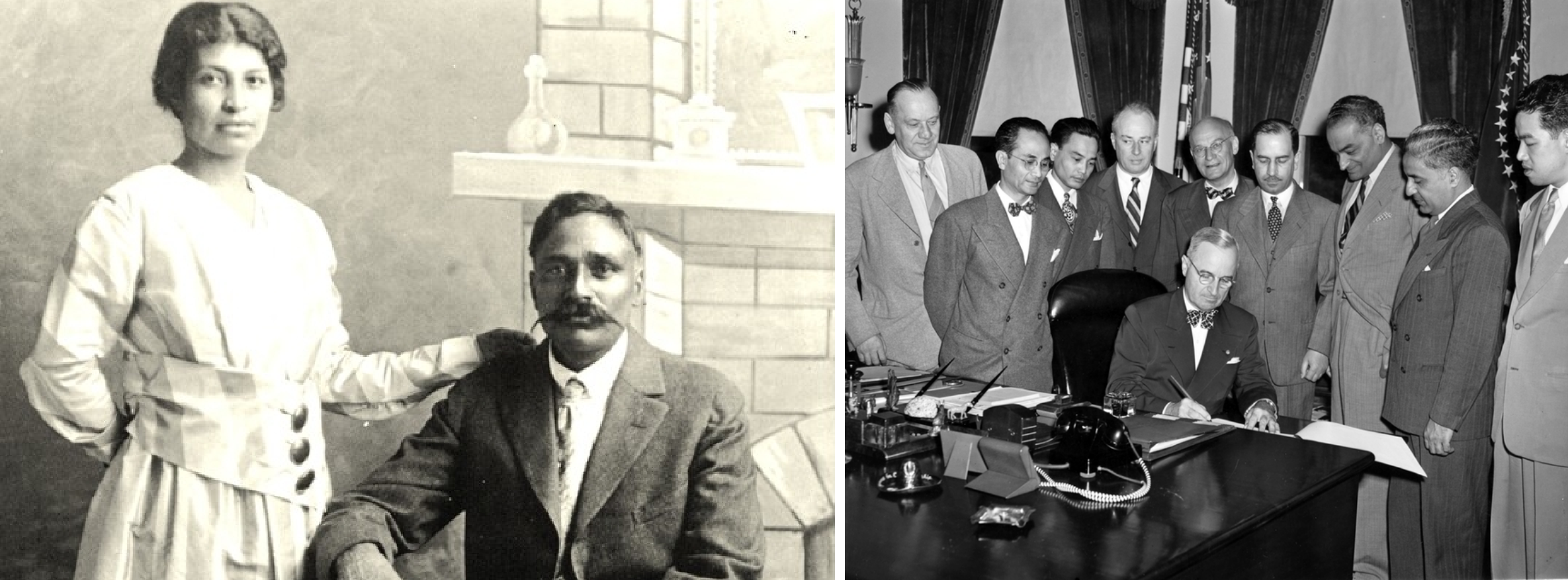

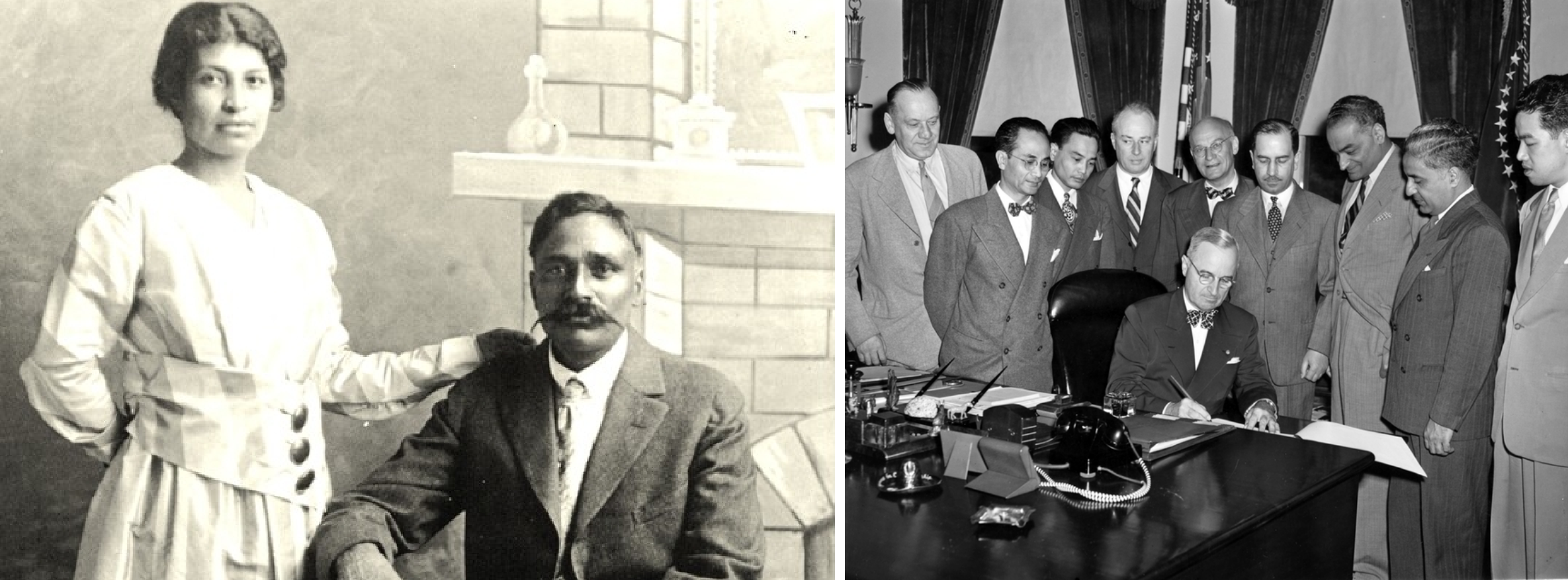

Left - Photo of Punjabi-Mexican American couple Valentina Alarez and Rullia Singh posing for their wedding photo.

Credit: Singh Yuba City, 1917 via Wikimedia Commons. (Public Domain)

Right - President Truman signed the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 that allowed a certain number of Filipino and Indian immigrants into the United States. This act affected the Punjabi-Mexican community as there were more opportunities for Indian men to marry Indian women.

Activity 3: Punjabi-Mexican Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Access to Land Rights

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the Discussion Questions. Encourage students to refer to the reading and to their notes.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If you prefer to have students discuss in small groups, you can create a worksheet using the questions above and distribute a copy to small groups. Be sure to review their responses as a whole class so that everyone has the opportunity to learn from their peers.

- Read this quote from the text: “The newly immigrated Indian women often looked down upon the Mexican women who had married Punjabi men.”

- Have students describe the context of this quote.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why would the newly immigrated Indian women look down upon the Mexican women?

- How is this not an example of cross-cultural solidarity?

- Why would the women not support each other?

- What would cross-cultural solidarity look like in this scenario?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: This is an example of how systemic racism pits cultural groups against each other. If communities of color are competing and fighting against each other, then they are too busy and weary to fight the system. Additionally, this manufactured division can keep them from jointly recognizing and addressing the root cause of the racism that targets them. In this context, it is less likely that communities of color would work in solidarity with each other and more likely that they would instead struggle alone in fighting for their rights.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: To learn more about early South Asian American experience, consider teaching The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “South Asian Pioneers in California”: https://asianamericanedu.org/early-south-asian-pioneers-in-california.html. In addition, PBS offers a resource entitled, “Roots in the Sand”: https://www.pbs.org/rootsinthesand/.

- Ask students: In what ways were Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities denied access to land and property and how did they work with other communities of color to resist such discriminatory and/or imperialistic practices and policies?

- If needed, provide students this chart to help summarize their thinking:

| |

How were they denied access to land rights?

|

How did they resist? |

Punjabi community |

|

|

Native Hawaiians |

|

|

Mauna Kea - Kiaiʻi/protectors |

|

|

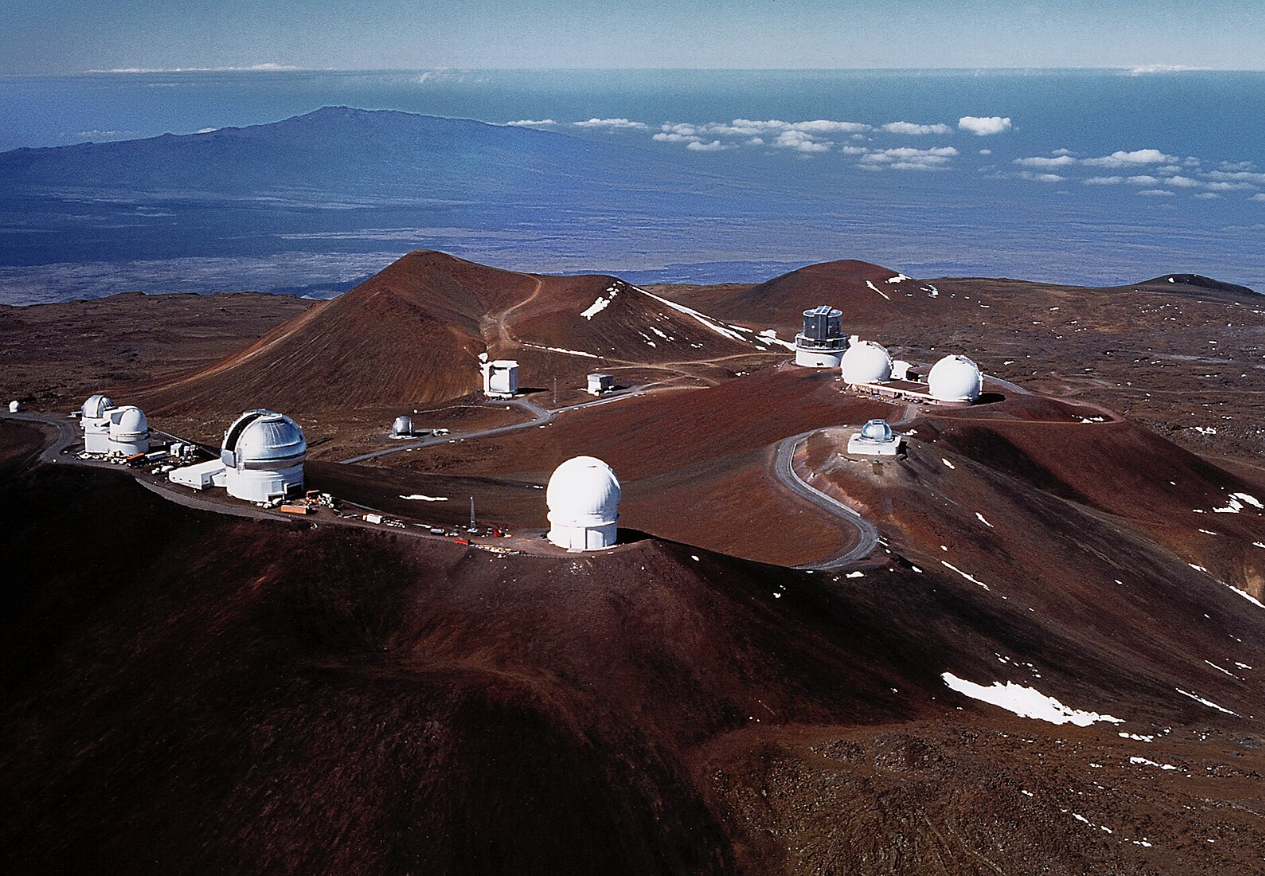

A view of telescopes on Mauna Kea, which is a sacred site for Native Hawaiians. Many land protectors protested the building of the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT), which led to the passing of a state law that would allow some authority from Native Hawaiians to protect Mauna Kea.

Credit: NOIRLab, “Aerial view of Mauna Kea,” Richard Wainscoat/International Gemini Observatory/AURA/

NSF (

CC BY 4.0 DEED)

Activity 1: Aloha ʻĀina: “Love of the Land”

- Share this statement: “Native Hawaiians, similar to other indigenous communities, don’t necessarily believe in private ownership of land. They believe their roles are more like stewards than owners. They live off the land and its natural resources. As such, they feel responsible for protecting, preserving, and restoring it. They believe in Aloha ʻāina which translates to ʻlove of the land.’ They believe that all things within and around this world are interconnected.”

- NOTE TO TEACHER: If time and if needed, show this video entitled, “Mālama ʻĀina: To take care of the land” to learn more about the concept of Aloha ʻāina: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9hkM9orsO4&t=272s

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Native Hawaiians are legally defined as descendants of the people who lived in Hawaiʻi prior to European contact in 1778. Native Hawaiians are indigenous to Hawaiʻi. Anyone living in Hawaiʻi even for generations is not “Hawaiian”; they are residents. Other folks are visitors or guests.

- Ask students the following questions: How is Aloha ʻāina contrary to the “American” conceptualization of land rights and land ownership?

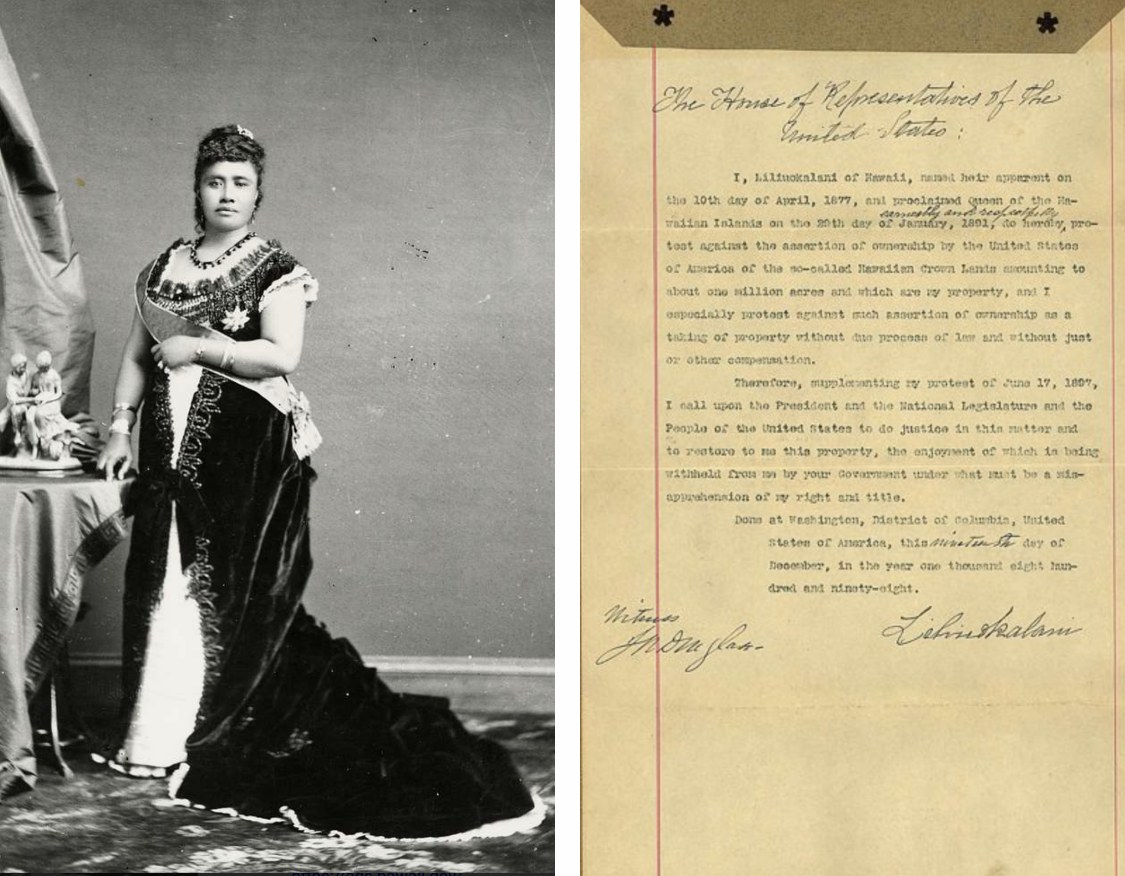

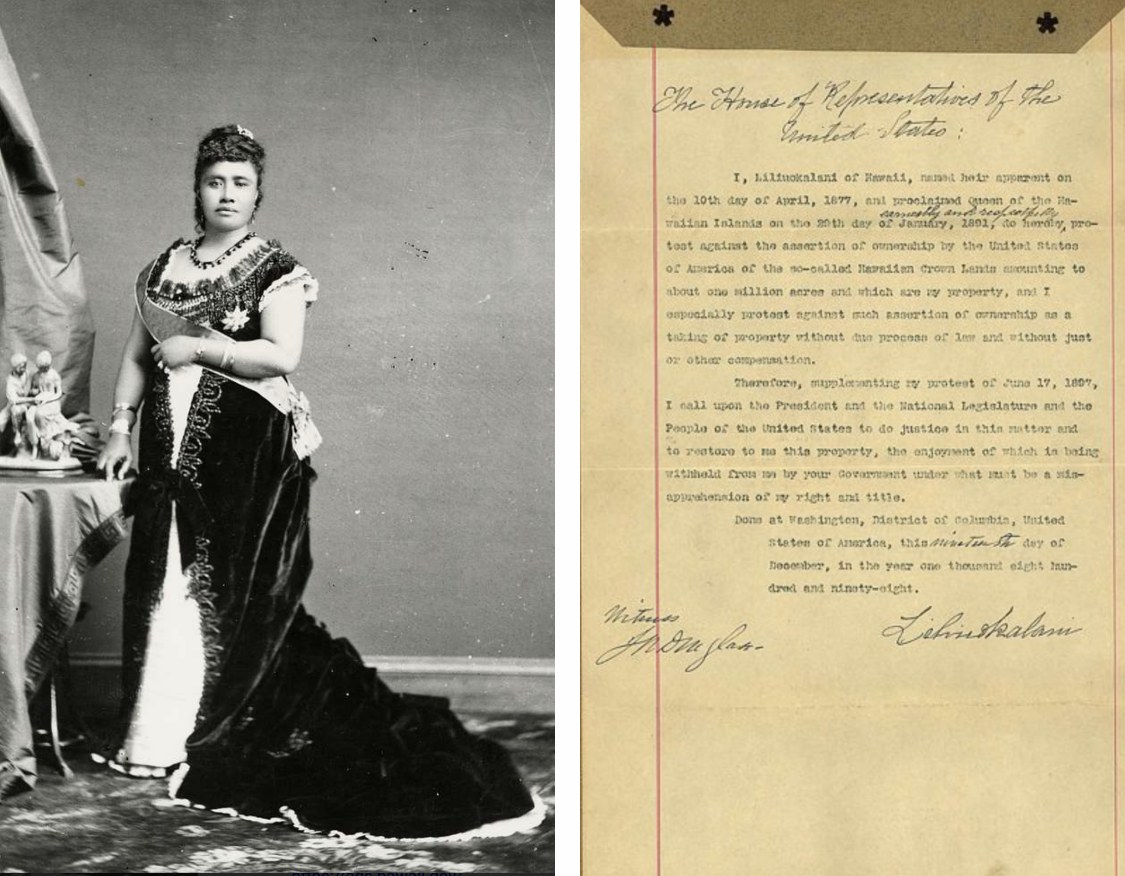

Left - A photo of Queen Liliʻuokalani, the first and last queen of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Right - Letter written by Queen Liliʻuokalani in protest of U.S. overthrow of Hawaiʻi.

Credit: U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Territories. (1898). “Memorial of Queen Liliuokalani in relation to the Crown lands of Hawaii”. National Archives Identifier 306653.

Activity 2: Letter from Queen Liliiʻuokalani

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Cornell Notes.”

- Tell students to watch the video and take notes. Tell them that videos are like texts and also need to be read, interpreted, and analyzed. Remind them that you had reviewed the Cornell Notes strategy in the previous lesson.

- Show this video entitled, “Queen Liliiʻuokalani - The First and Last Queen of Hawaiiʻi”: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/queen-liliuokalani-the-first-and-last-queen-of-hawaii-kx2oc7/15032/#

- Direct students to read the text and complete the “Cornell Notes” worksheet as they read.

- Have students write the source information in the top row. Tell them to record the title, author, and date of publication.

- Have students record notes as they read in the right column. Tell them to define any unknown words, write down important key phrases, etc. Encourage students to paraphrase, use abbreviations, use symbols, etc. Encourage students to also take notes on the actual text by underlining important ideas and circling any confusions. Encourage them to write notes in the margins as well.

- Have students complete the left column after they are done reading. Tell them to look for patterns in their notes (in the right column) and write down main ideas. Also, tell them to write down their questions in the left column.

- Have students complete the last row after they have finished the rest of the worksheet. Tell them to summarize their reading by using their notes.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What did you learn from the video?

- What happened to Queen Liliiʻuokalani and why?

- How did Queen Liliiʻuokalani resist?

- Why is Queen Liliiʻuokalani an important figure?

- Share the following statement: “While imprisoned in her own house, Queen Liliiʻuokalani wrote many letters in support of Hawaiian sovereignty. She tried to build allyship with politicians.”

- Distribute the text and worksheet entitled, “Primary Source: Letter from Queen Liliiʻuokalani.”

- Work with students to read the letter and complete the worksheet:

- Note the title, author, date, and source of the text.

- Record observations in the left column.

- Record questions in the right column.

- Annotate as you read by highlighting or underlining important ideas and circling confusing vocabulary and concepts.

- Complete the reflection questions at the end of the worksheet.

|

Strategy: Analyzing Sources

(Observe, Reflect, Question Strategy)

Primary and secondary sources can be complex texts. But, they are necessary for historical thinking. Both sources complement each other in order to help learners build convincing arguments. Teachers can help students by providing prompting questions as they read.

For more on analyzing sources, see:

|

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What are the historical and political contexts of the letter?

- What was Queen Liliiʻuokalani trying to achieve with this letter?

- Who is she directing the letter to?

- What claims is she making?

- How is she trying to build solidarity? And with whom?

- Think about the Mauna Kea protest. What do you think would have happened if Queen Lili’uokalani had access to social media?

- Display a copy of the original letter and ask the following questions:

- How does seeing an image of the actual letter enhance your understanding of the content and context?

- What is typed and what is handwritten? What is the significance of this?

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Many of Queen Liliiʻuokalani’s letters are available online. Her letters to the U.S. government are examples of her attempt to build allyship and support for her cause. Encourage students to read more of her letters. Tell students that the Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement continues today. If time permits, show students this PBS video clip entitled, “Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement”: https://vimeo.com/685585262. If needed, consider teaching The Asian American Education Project’s lesson entitled, “Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement”: https://asianamericanedu.org/3.3-Native-Hawaiian-Sovereignty-lesson-plan.html

Activity 3: Continuity and Change

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue.”

- Tell students that enduring issues are issues that exist across time.

- Direct students to brainstorm a list of enduring issues related to land rights.

- NOTE TO TEACHER: Enduring issues related to land rights could include the conquering and colonizing of indigenous lands and people, the denial of lands to immigrants and/or communities of color, etc.

- Have students select an enduring issue related to land rights and record it in Part 1.

- Work with students to complete Part 2 and Part 3 of the worksheet:

- Identify three characteristics of the enduring issue in the left column.

- Write how each community interacts with each characteristic in the middle three columns.

- Identify and record information that helps you to establish what has changed and what has remained the same over time in the fourth column.

- Have students complete Part 3 of the worksheet and then use the prompts to facilitate a discussion: (See Answer Key: Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue)

- What is one example of a continuity for this enduring issue?

- What is one example of a change for this enduring issue?

- Was there greater continuity or change for this issue over the course of these events?

|

Strategy: Continuity and Change for an Enduring Issue Tool

The theme of continuity and change is a major concept in the study of history. Historians often organize

their thinking about the past by examining what has changed (change) and what has stayed the same

over time (continuity). They also examine the underlying reasons as well as the effects of changing, or of

not changing.

For more on teaching Continuity and Change, see:

|

- Ask students: How did the examples of cross-cultural solidarity in this lesson compare to the previous examples of cross-cultural solidarity? How are they similar? How are they different?

- Ask students: What issues of land or property rights are happening today?

- If you are teaching this lesson as part of the Cross-Cultural Solidarity unit: Summarize this set of lessons by sharing this statement: “We examined the enduring issue of land rights and how people in power acquire and use land as a way to disadvantage and subjugate communities of color. However, working in solidarity, some communities have been able to successfully resist.”