“The Crisis” is a quarterly magazine founded by the NAACP in 1910 and its founder is historian and sociologist W.E.B Du Bois. Du Bois stated that the purpose of “The Crisis” was to "set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people."

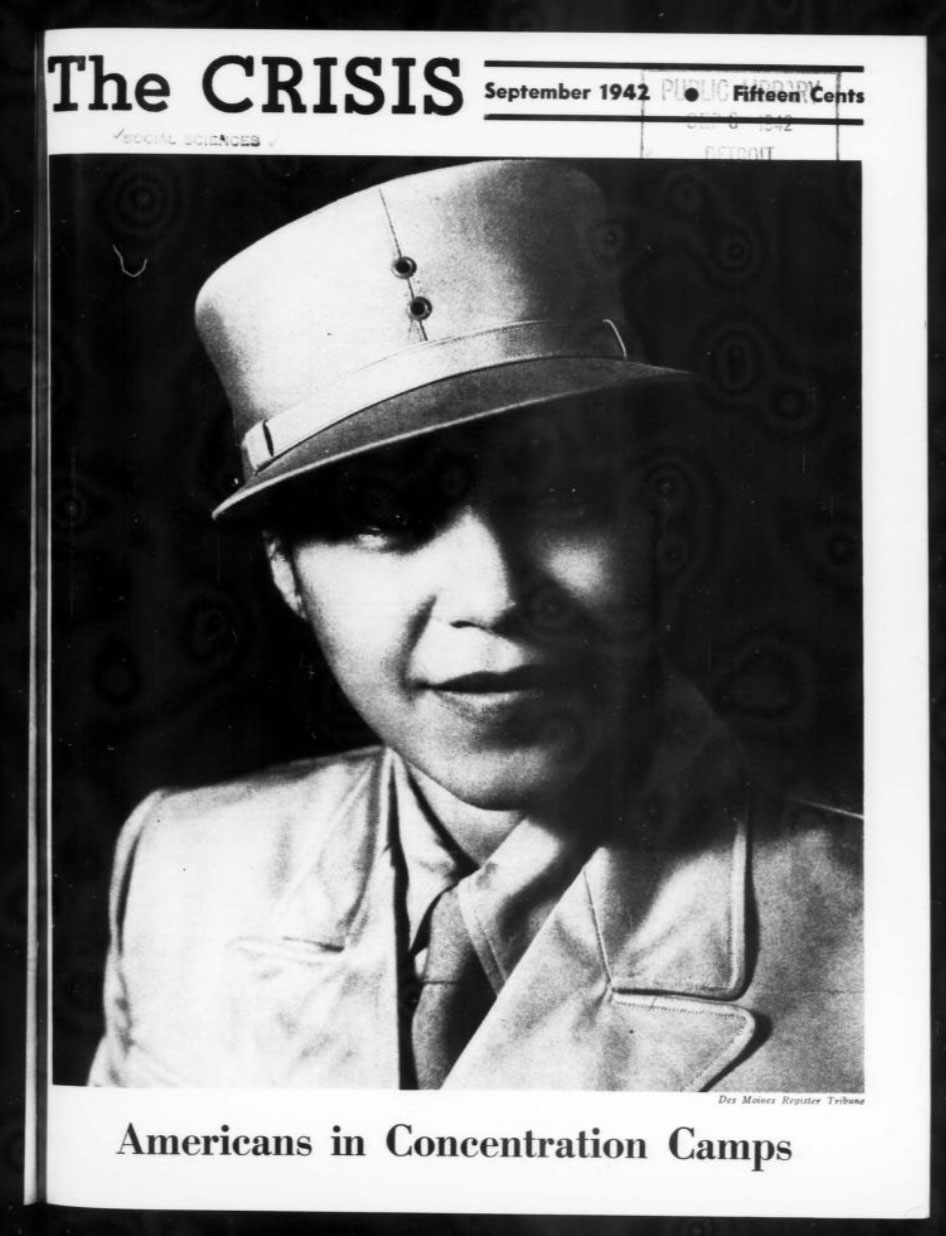

Americans in Concentration Camps

Color seems to be the only possible reason why thousands of American citizens of Japanese ancestry are in concentration camps. Anyway, there are no Italian-American, or German-American citizens in such camps.

Over 70,000 native Americans, citizens born, are now lodged in concentration camps in the American West, with no criminal charges of any kind against them. No court has found them guilty of any offense against American law; indeed, no formal indictment has ever been drawn up against them. It is acknowledged that the great majority of them are loyal, law-abiding Americans, true to the country of their birth. Some of them have given most useful assistance to the American government against enemy spies and other agents. Even in their present situation, most of them are trying bravely to make the best of things, and are willing to accept the government’s explanation of “military necessity.”

Why are they there? First of all, because the United States is at war, and the Army has secured tremendous power in national affairs. The hapless citizens who have been deprived of their constitutional rights and constitutional protection have the misfortune to include among their ancestors persons of a nonwhite country with which the United States is now at war. It is the “non-white” which must be emphasized. American citizens of German, Italian, Hungarian, Bulgarian, or Roumanian ancestry have not been legally discriminated against. It is only our citizens of Japanese ancestry who have been put into concentration camps. They are not “white.” They are “not to be trusted.”

There are also some 40,000 “enemy aliens” in the same camps. These aliens also are not “white.” If they were “white,” the great majority of them would not be aliens at all. Most of them have been in this country over thirty years ; their average age is sixty-three years. But they have not been permitted to become American citizens, as they are “Asiatics.” During the generation and more that they have been in this country, over a million Germans and Italians have entered the country and been naturalized as American citizens. German Nazis and Italian Fascists are “white”—whatever their politics. But American naturalization laws, as interpreted by the United States supreme court, deny the right of naturalization to Asiatics. So Asiatic immigrants remain “aliens.” If we are at war with their homeland, they become “enemy aliens” —including hundreds who fought in the American armed forces in the first world war! They are “aliens” only because America has refused them citizenship.

Italian-American vs. Japanese American

Along the eastern coast of the United States, where the number of Americans of Japanese ancestry is comparatively small, no concentration camps have been established. From a military viewpoint, the only danger on this coast is from Germany and Italy. Enemy submarines are carrying on a terribly successful war against American shipping along the coast. They have landed agents along the coast, some of whom have been apprehended. But the American government has not taken any such high-handed action against Germans and Italians— and their American-born descendants— on the east coast, as has been taken against Japanese and their American-born descendants on the west coast. Germans and Italians are “white.”

Illustrative of the situation, and in some significant ways symbolic, was the great “New York at War” parade on June 13. Mayor LaGuardia, New York’s capable and energetic chief executive, was in charge. It was a most spectacular and comprehensive affair, including not only American and Allied forces and delegations but loyal German-Americans and Italian-Americans. It even included Soviet Russians—whose loyalty to the war against Hitlerism dates only from June 22, 1941, when Hitler invaded Russia. Together with our Italian-American mayor on the official reviewing platform were our capable Jewish governor, our “Nordic” vice-president, and the Fascist King of Greece—now transformed, like Stalin, into our “ally.” It was both representative and significant.

There was one little omission in the parade. Americans of Japanese ancestry were not permitted to take part. A group of them, of unquestioned loyalty, were turned down flatly while Germans and Italians marched proudly up Fifth avenue. Four members of the American Civil Liberties Union—Miss Florina Lasker, chairman of the New York City committee, Rev. John Paul Jones, Mary Dreier, and Guy Emery Shipler (editor of The Churchman)—sent a shocked and indignant protest to Mayor LaGuardia and Police Commissioner Valentine:

“We learn with amazement that the committee in charge of the patriotic parade in support of the United Nations on Saturday has refused to permit loyal Japanese-Americans to march, although permitting German-Americans and Italian-Americans to participate. Such discrimination on purely racial grounds is a shocking violation of our democratic professions.”

Mayor LaGuardia did not deign to reply. It was, indeed, a somewhat embarrassing question for him. How did it happen that an American of Italian descent should bar Americans of Japanese descent? Their “national” position was precisely similar. And there was no doubt of the loyalty of either. But he was “white” and they were “colored.” It made a difference.

It was at the end of March—almost four months after Pearl Harbor—that the Army started the forcible removal of west coast Japanese and Japanese-Americans to concentration camps. It was not due to some urgent and pressing “present danger” ; things were more fully under control along the Pacific Coast than they had ever been before— and far more than they had been during the previous December. It was not due to the sudden shock and hysteria occasioned by Pearl Harbor itself—that had long passed. Neither was it due to any new revelations regarding Japanese espionage or sabotage in American territories ; the wild rumors about widespread Japanese sabotage in Hawaii had been officially disproved. The Tolan committee had received an official statement from the Honolulu Chief of Police, W. A. Gabrielson, stating clearly and without qualification : “There were no acts of sabotage committed in the city and country of Honolulu on Dec. 7, nor have there been any acts of sabotage reported to the Police Department since that date. . . . There was no deliberate blocking of the traffic during Dec. 7 or following that date by unauthorized persons.”

Possibilities of sabotage, indeed, were pretty well disposed of along the Pacific Coast during the weeks and months after Pearl Harbor. Loyal Americans of Japanese descent, and Japanese residents loyal to their new homeland, had given full cooperation to the American authorities in tracking down Japanese spies and agents along the coast. By the end of March, these creatures seemed to have been pretty well cleaned up. The propagandist Japanese-language schools, which our authorities had permitted to carry on despite criticism from democratic Japanese, were at long last closed down. But then, at the end of March, the Army clamped down on the loyal Japanese-Americans and put them into concentration camps. (There may be a “moral” to this, but it’s not a “good” one ; it does not assist the current line that the “Japs” are treacherous.)

Down to March 29, the Western Defense Command under General DeWitt had encouraged voluntary evacuation of Japanese-Americans from the coast into inland states. On that date, however, the command reversed itself ; General DeWitt forbade further voluntary evacuation, and ordered persons of Japanese ancestry to stay where they were at the time. Later, they were moved by the Army. They were forced to liquidate their farms and their little businesses at ruinous prices. White speculators, farmers, and business men took over their farms and shops. Second-hand men and junk dealers got the contents of their homes. It was a famous victory.

Though there were only a few hundred of these contemptible profiteering creatures, they were aided by various forces. Race prejudice is still a factor along the coast, and was exploited to the utmost by the foul press—particularly that of Hearst and Otis,—featuring absolutely false statements about “what happened in Hawaii” and the “Yellow Peril.” Local politicians had competed with one another in showing their courageous patriotism by reviling the “Japs.” The Associated Farmers and Chambers of Commerce cooperated with those of their members who were eager and anxious to plunder their yellow-skinned competitors. And there was widespread ignorance, as large numbers of persons had never come to know any of the Japanese-Americans, and were worked into actual fear and hysteria by the anti-Japanese blasts of the press and radio. Even among the Negroes along the coast, many failed to realize that the issue was basically racial, and directly concerned themselves.

The Army was not wholly above these things. If it was immune to the pressure politics of Farmers’ Associations and Chambers of Commerce, it was certainly not immune to race prejudice, nor indifferent to the American Legion. Nor was it interested in contradicting the anti-Japanese propaganda of the press and radio, which presumably helped “morale” and the war effort. And it had pretty definite aims of its own—the extension of military authority over as wide a field as possible, supplanting civil authority everywhere the opportunity offered. In Hawaii with its great colored majority, which has never been given State’s rights and still remains a territory, the Army obtained absolute powers from the President on December 7, since which time the military dictatorship there has extended even to the criminal courts. Army authority, it should be added, is Federal authority.

There was, however, another factor present in March. Army and Federal government officials, in private conversations, expressed real apprehension of Japanese reprisals against American prisoners-of-war if Japanese were lynched in the United States. The increasingly rabid fury of anti-Japanese invective, and the murderous howling of the “Vigilantes” for yellow meat, seemed to presage some terrible outbursts. Lynchings had to be prevented ; for this, it was necessary to herd Japanese and Japanese-Americans into concentration camps—“for their own protection.” A high official in Washington said gravely to a representative of the Federal Council of Churches : “It is a sad commentary on the American way of life when we find it necessary to put American citizens behind barbed wire in order to protect them.”

There was, certainly, direct association between the Army’s moves and the war situation in the Far East. On March 25, the Japanese had launched their final overwhelming drive against the Filipino and American defenders of Bataan—half-starved, most of them sick and without medicines, watching daily for reinforcements and supplies which never arrived. The government knew the end was near ; MacArthur had already left for Australia ; by March 26 it was clear that Bataan could not last another two weeks—though the soldiers were not told this. On March 29 came the Army’s order on the west coast, reversing its previous orders and forbidding further voluntary evacuation. Members of General DeWitt’s staff gave as a reason his fear lest the evacuees suffer physical violence on account of the strong hostility to them in many communities east of the First Military Area. Events on Bataan soon made clear why this fear developed at that particular moment. By April 10, several thousand sick and starving American prisoners were in Japanese hands—and several times that number of Filipino prisoners.

If General DeWitt’s idea was really to protect Japanese-Americans from their white fellow-citizens, he must be given due credit. It must be noted, however, that this laudable impulse does not seem to have developed until it became certain that the Japanese would soon have thousands of American prisoners in their hands—upon whom reprisals might be taken. The lynchings of yellow Americans would be no light matter if it were countered by shootings of white American prisoners by the Japanese. Japanese-Americans had to be protected—not for their own sakes, but for the protection of American soldiers in Japanese hands. The Japanese now had American hostages for our good behavior.

There was, indeed, another way out. The government, with its thousands of official censors and propagandists, could have clamped down on the Hitler-like racial fury of the anti-Japanese press, could have given wide circulation to the facts regarding Pearl Harbor and the splendid loyalty of most Americans of Japanese descent, could have emphasized Secretary Hull’s official statement that he expected the Japanese reply to his note of November 26 to be “war,” could have stressed the fact that Washington had notified Hawaii on November 27 that negotiations with Japan “had ended” and that an attack was to be expected at any time. But this would have gone counter to the official propaganda about “Jap treachery,” and might not have helped war morale. So, instead, we slapped the “Japs” into concentration camps—for the protection of American soldiers in Japanese hands. So our Army also got some “prisoners’’—and hostages.

If the Army’s aim was the protection of Japanese-Americans, this aim seems to have been forgotten as soon as the evacuees were got into the pleasantly-named “reception centers” and “assembly centers.” They were treated as dangerous aliens, and their accommodation was of the worst. The Army was in charge, and it was almost impossible to obtain permits to leave ; the Army accused evacuees of “trying to escape” (from “protection!”). Ten thousand or more persons would be confined to an area of less than a square mile, sometimes surrounded by barbed wire and always by armed guards. At Manzanar and some other centers the guards would not permit parcels—soap, clothing, shoes, baby things—to be brought into the camp. For a long time such urgent necessities as goggles—to keep dust from the eyes in windy and semi-desert centers—could not be brought in.

There was no direct torture. It was an American, not a Nazi, concentration camp. Some of the older inhabitants— most of the Japanese-born were over sixty—suffered from insufficiency of their customary rice. Persons accustomed to daily bathing and the most scrupulous cleanliness found it “troublesome” to live in filth, lacking tubs, buckets, washing machines, or sufficient soap. Perpetually dusty and dirty eyes were painful and “troublesome.” Babies found unwashed diapers painful as well as odorous. Parents suffered as their children sickened and died, living in a filth and squalor such as neither they nor their ancestors had known within their long memories. But there was no “torture.”

Not all the evacuees were yellow. There were some white and other non-Japanese— mostly women married to Japanese-Americans. And some of the Japanese-Americans were not more than one-eighth Japanese, owing to intermarriage. But a “Jap” was anyone with traceable Japanese blood—just as Hitler’s “Jews” means anyone with traceable Jewish blood. A Japanese grandfather is as valuable to an American in California as a Jewish grandfather to a German in Berlin—or a Negro grandfather in Atlanta. Some of the women— Americans of Japanese descent—were separated from non-Japanese husbands who could not or would not make the sacrifice of following them into bondage.

Housing conditions vary in the different camps. Usually the houses are long barracks, with a single community toilet and laundry for a block of houses with hundreds of persons. At Manzanar and some other centers, the houses are built of rough lumber ; dust seeps in continuously. At Manzanar there are two to three families, or eight to ten persons, to a room—assigned regardless of age or sex. The population density of Manzanar is about 30,000 persons per square mile—equal to that in Metropolitan New York.

There is no running water in houses in most of the camps. At Manzanar only two of the twelve blocks of houses have hot showers in the community toilet, and hot water for dishwashing. For weeks, there were almost no laundry and washing facilities—in a dusty and windy area, for a people accustomed to daily bathing at all times. At Puyallup, to the north, there was one small washroom for every 250 persons ; an endless line was standing and waiting at all times—in a broiling sun most of the day, and with no shade. It is not so dusty at Puyallup. The dirt does not come through the walls, but from the ground. The shacks are laid flat on the ground, and mud oozes up through the floors during and after the frequent rains. But the roof is only plank plus tarpaper, so the sun soon bakes the mud—and the inmates. Sometimes the sewage-disposal pipes break, and the sewage flows down the streets. Children play in the filth— they must play somewhere. But there is no “torture.”

Food is adequate. Anyway, no one has died of starvation. But some old persons, accustomed to rice and vegetables, cannot digest stale bread and canned wieners and beans. Tea is their great solace—but some of them cannot drink it when it is dosed with saltpeter, as is done at Camp Harmony and some other “resorts.” Also, some of them find it difficult to stand in line for half an hour or more, in the long mealtime queues, out in the rain with their feet in the mud, or in the fierce sun farther south, waiting for their miserable portions of canned foods. They grew beautiful vegetables, of course. But other persons are eating them—when they are being eaten. Sometimes the patriotic whites who grabbed their farms simply plowed the vegetable crops under, not knowing how to handle them.

What has happened to these Amercans in recent months is of direct concern to the American Negro. For the barbarous treatment of these Americans is the result of the color line. This cannot be too often repeated or too clearly understood. These men, women, and children have been taken from their pleasant homes and long-cultivated farms and businesses because their skins are yellow and their eyes have the tell-tale Mongolian eyefold. Americans of German or Italian descent are not being discriminated against. Wendell Willkie and Fiorella LaGuardia are not being stuck into filthy and noisome shacks in vile concentration camps because they are of German and Italian ancestry ; they are white. Old Germans and Italians who have lived in the United States for a generation are not being discriminated against ; they are white, and most of them are citizens. Even the Germans and Italians who have reached these shores during the past twenty years are not treated as “enemies.” Many of them, in fact, are giving loyal service to their adopted country ; these services are welcomed. They are white.

Negroes have been told again and again : “Work quietly, be industrious, mind your own business, and you will get justice even in America.” That is what these yellow-skinned Americans believed. They worked, cheerfully and industriously. They turned deserts into beautiful and fertile farm-land, grew vegetables and fruits for themselves and for others. They distinguished themselves at school, abstained from politics, had the lowest crime-rate of any group in the entire country. They earned the respect of all decent white persons who came in contact with them, overcoming racial prejudice among tens of thousands ; many of these tried ineffectively to help them during recent months ; most significant is the fact that there have actually been no lynchings, and that Japanese-Americans felt safe in their own American communities where they were known. They did not ask for the Army’s “protection ;” it was thrust upon them.

What has been their reward? They have been plundered of everything, and crowded in concentration camps fit only for pigs. If Westbrook Pegler and the southern senators have their way they will be deported to Japan when the war is over. There is already a move to deprive them of citizenship—a move headed by the “Native Sons of the Golden West” and the Senate’s Immigration Committee. If this move is successful, it would disfranchise not only Japanese-Americans but other “Asiatics.” It is using as its basis, indeed, an 1898 court decision disfranchising an American of Chinese descent— later overruled by a majority United States supreme court decision. And if native-born Americans, of Asiatic descent, can be denied all civil rights and civil liberties, what about Americans of African descent?

Down to the Civil War, American citizenship was for “free whites.” The Fourteenth Amendment ended this limitation—on paper—and racial limitations on citizenship were formally abolished. It has taken a long while to approach this. Most American Negroes are still disfranchised—by poll tax or other restrictions in the states where they are most numerous. But much has been gained, and colored Americans are now struggling with increasing success for a position of political equality.

The drive against Americans of Asiatic descent is a direct counter to this. It is significant that southern senators and congressmen are among the most rabidly anti-Japanese. For if Asiatic-Americans can be reduced to bondage, deprived of citizenship and of property, the same thing can be done to Afro-Americans— and to Jews.

This is an integral part of the struggle for human and racial equality. It concerns every Negro. It concerns every believer in democracy and human equality, regardless of color. “For even as ye have done it unto the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”

I watched a tongue of lighting last night,

It was as if God had leaned forward

The better to see the wet city,

And in doing so, caught the gleam in His

eyes.

-William Smallwood