Japanese American incarcerees work at an adobe factory. The biggest work project at the Poston Incarceration Camp was the construction of adobe school buildings.

Credit: Photographer: Francis Stewart, 1943. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Grade: 9-12Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Lessons/Activities: 7

While incarcerated at Poston Incarceration Camp during World War II (1939-1945), Japanese Americans were forced to work on several projects, including irrigation-related projects and the building of adobe school buildings. In this lesson, students will learn about the contributions that incarcerated Japanese Americans made to the irrigation, agriculture, and buildings on the Colorado River Indian Reservation (CRIR). Students will watch a clip from the narrative film The Blue Jay to examine the relationship between a fictional Japanese American and Indigenous Mohave Indian. They will analyze primary sources written by Japanese American children at Poston.

Students will:

- Evaluate the impact of Japanese American laborers on the environment of the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

- Analyze primary sources to learn about the experiences of Japanese American children incarcerated at Poston.

Experiences of Japanese Americans and Native Americans at Poston Essay:

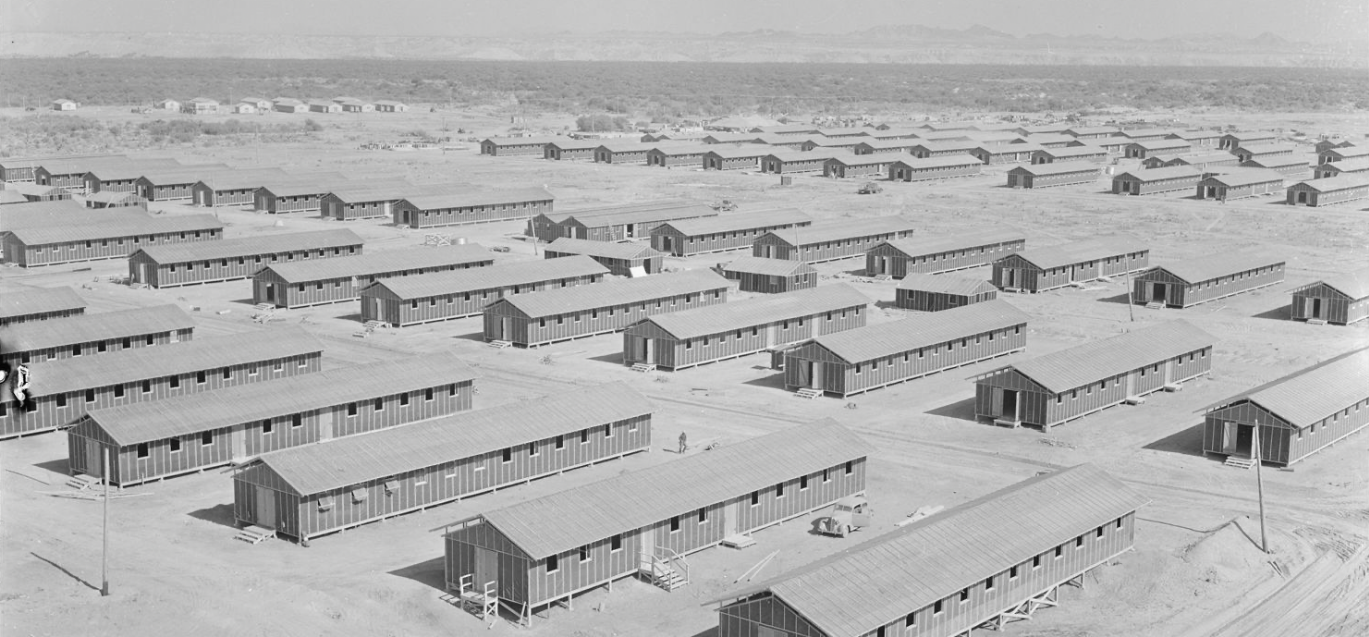

During World War II (1939-1945), roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to

incarceration camps. There were five requirements for setting up the incarceration sites: (1) The site must be on public land, (2) The site must be adequate for large projects, (3) The site must provide work opportunities throughout the year, (4) The site must be located at a safe distance from strategic work (e.g. military bases), and (5) The site must have satisfactory transportation and power facilities, water supply, and climate.

Incarcerees in Poston lived in guarded

compounds. The

barracks were divided into one-room “apartments.” Partitions between apartments left a gap between the walls and the roof, such that conversations could be heard between them. The camp barracks were arranged in blocks, with fourteen apartments per block. Each block had a

mess hall, separate public bathrooms for men and women, a laundry and ironing room, and a recreation building. In the fall of 1942, living conditions were harsh, as the barracks were unheated. Promised clothing had not been delivered. There were food shortages. Sadly, the housing at Poston Incarceration Camp was considered better than that available to the Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT) at the time, which often lacked electricity, flushable toilets, and showers.

Hundreds of incarcerees worked on

irrigation-related projects at Poston. In fact, the Japanese Americans constructed an irrigation system that is still in use today. They also set up farms in the camp. The WRA had

leased property from the Colorado River Indian School for farming. Many of Poston’s incarcerees were from the farm regions of Central and Southern California, and had experience with farming. The farmers cleared and irrigated the land, and grew crops such as cantaloupe, lettuce and spinach. They also raised chickens and hogs on the farmland.

The biggest work project at the Poston Incarceration Camp was the construction of

adobe school buildings. This project faced many challenges from the beginning. It was difficult to recruit workers for the adobe brick factory. Authorities at the camps tried to persuade the Japanese American incarcerees to help build the school buildings for their children, though this was misleading because the ultimate purpose of the buildings was to serve Native American children after the war ended. Women took on much of the work initially. Children were also recruited to work.

Many of the incarcerees were inexperienced, having never worked as carpenters or in construction. The WRA also faced challenges in obtaining the construction materials needed to build the schools. In addition, the general public in Colorado felt that public tax money should be spent on public schools and not building schools in the camps. Later, the project was further derailed as Japanese Americans were allowed to relocate to other camps. Some found employment in states outside the Western region. Some enrolled in military service.

Meanwhile, school started in the fall of 1942 for incarcerated children. Barracks were initially used as classrooms but they lacked tables and chairs. Laborers worked overtime to make tables in time for the school opening, but it was impossible to make chairs in time, and so the students carried folding chairs to school each day. The Poston schools also lacked adequate supplies of books, writing materials, and other necessary items.

A group of junior high and high school students compiled essays and poems into an album called Out of the Desert and sent it to pen pals at the American Junior Red Cross. They wrote about their experiences and daily activities. They described the harshness of the desert and the difficulties of attending school. Just miles away, Native American students at the Colorado River Indian School also wrote about their experiences in their school newspaper. They wrote about the war and its impact on their reservation.

Students from both schools had little contact with each other except for occasional basketball games. These games became a rare occasion for Japanese American and Native American students to connect. However, for most of the adults, the interaction between the CRIT community and the Poston incarcerees continued to be limited. Armed guards were posted at a canal that separated the reservation from where the incarceration camps were. Officials told Native Americans not to interact with the incarcerees. There are some accounts of Japanese Americans and Native Americans meeting and trading goods, but this was the exception, not the norm.

As World War II progressed, internal disagreements simmered between the WRA and OIA. Dillon Myer (1891-1982), the WRA Director, believed that Japanese Americans should completely

assimilate into White American culture and society (known as the “melting pot” theory). As such, he implemented policies that pushed Japanese Americans to leave the camps for employment outside of the Western region, thus greatly reducing the Poston workforce. This was at odds with the OIA Commissioner, John Collier (1884-1968), who believed that

minority groups should be allowed to preserve their cultures while living in the

dominant culture (known as “cultural pluralism”). On August 11, 1943, Wade Head (1907-1997), the Poston Project Director, wrote to Collier and recommended the OIA cut ties with the WRA because he felt the OIA was being forced to implement policies that were in conflict with Collier’s beliefs.

The OIA officially turned over the administration of Poston to WRA on December 31, 1943. By this time, the Japanese American workforce had completed construction of an irrigation system to the southern region of the CRIR. They built a hard-surface highway to the city of Parker, gravel-surfaced roads for the farm area, and built bridges for the irrigation canals. They leveled the land for agricultural use and produced food crops for the incarcerees. They also completed the construction of fifty-four adobe school buildings that would later be used for the future Indian Service program.

This text is an excerpt from the “Sharing a Desert Home: Life on the Colorado River Indian Reservation” by Ruth Y. Okimoto. It has been adapted for reading accessibility and clarity. Access to the original text can be purchased through the Poston Community Alliance.

Bibliography:

Okitomo, Ruth Y. (2001). Sharing a Desert Home: Life on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books.

- Adobe: a building material used to make bricks

- Assimilate: to absorb into the cultural tradition of a population or group

- Barrack: a building or set of buildings used especially for lodging soldiers

- Colorado River Relocation Center: the term used by the War Relocation Authority to identify the Poston “internment site” to detain Japanese Americans

- Compound: a fenced or walled-in area containing a group of buildings

- Dominant culture: the culture, norms, and practices that are viewed as the standard within a society; in the United States, the dominant culture is White/European American

- Incarceration: confinement in a jail or prison

- Irrigation: the watering of land by artificial means to foster plant growth

- Lease: to rent out a piece of land or property for a specified term and for a specified rent

- Mess hall: a hall or building where people eat together, usually on an army post

- Minority: a small group relative to the general population; commonly used to refer to non-White groups; today, other terms are generally preferred such as people of color, BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color), and others

- Poston Incarceration Camp: the term currently used for the “Colorado River Relocation Camp” to convey that the camps were concentration camps where U.S. citizens of Japanese descent were denied due process, freedom, and their Constitutional rights

- Reservation: a federal Indian reservation is an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe.*

- Tribe: a social group composed chiefly of numerous families, clans, or generations having a shared ancestry and language

- What were living conditions like for Japanese Americans incarcerated at Poston Incarceration Camp?

- What work projects did Japanese Americans work on at Poston Incarceration Camp?

- What was school like for children at Poston Incarceration Camp?

- What contact did Japanese American children have with Native American children?

Japanese American incarcerees sign up for the War Relocation Authority Work Corps. One of the requirements for incarceration sites was that the site must provide work opportunities throughout the year.

Photographer: Fred Clark, 1942. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Activity 1: Accessing Prior Knowledge about Poston Incarceration Camp

- Have students review learning from Lesson 1 by discussing the following questions:

- Why were Japanese Americans incarcerated?

- What groups were involved in the establishment of the Poston Incarceration Camp? What were the goals of each group?

- What is the geography of the Colorado River Indian Reservation (CRIR), and how did its geographic characteristics impact each group’s goals?

- Tell students that both essays in Lesson 1 and Lesson 2 mention the five requirements needed for establishing incarceration sites. Have students complete the worksheet entitled, “Requirements for Incarceration Sites.”

- Review the worksheet responses and facilitate a discussion by asking: Which requirement do you think is the most significant and why? Who benefits from each of these requirements?

Activity 2: Analyzing The Blue Jay - Part 2

- Have students recall their takeaways from Part 1 [0:00-5:16] of the film from Lesson 1.

- Ask students, “Why was the initial relationship between Sam (the Japanese American) and Pohache (the Native American) a bit contentious? How does history play a part in their interactions?”

- Show a clip [5:17-9:54] from the film, The Blue Jay.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How does the relationship between Sam and Pohache develop?

- How does the film portray government corruption? What is the significance of showing this corruption in the film?

- Why does Pohache refer to Sam as “the enemy”? (9:09) What does he mean by this?

Activity 3: Examining Japanese American Impact on the Colorado River Indian Reservation

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Discussion Questions listed above.

- Create and display the chart below for all students to see:

| |

Japanese American Impacts on the CRIR |

Who Benefits? |

| Irrigation |

|

|

| Agriculture |

|

|

| Buildings |

|

|

- Have students reread the essay and find information on how incarcerated Japanese American laborers impacted the irrigation, agriculture, and buildings on the CRIR. Record student responses in the middle column.

- Facilitate a discussion about who benefits from these impacts. Record student responses in the right column.

- Have students watch a clip [9:57-11:24] from the video entitled, “Sharing a Desert Home.” Have students share what they learned and add responses to the chart.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the following questions:

- In what ways did incarcerated Japanese Americans impact the geography of the CRIR?

- How did this meet the plans and goals set forth by the WRA and OIA at the start of WWII?

- How were the Native Americans on CRIR affected?

A group of children play cards at Poston Incarceration Camp.

Credit: Photographer: Francis Stewart, 1943. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Activity 4: Analyzing Primary Sources: Japanese American Perspective

- Tell students that original writings from junior high and high school students at Poston were compiled in an album called Out of the Desert and sent to pen pals at the American Junior Red Cross. Have students access Out of the Desert.

- Ask students what they think they could learn from these primary sources. If needed, remind students that primary sources are firsthand accounts of an event created by people who experienced or witnessed the event.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Primary Source Analysis: Out of the Desert.”

- Have students read pg. 4-10 of the document to gather information for Parts 1 and 2.

- Have students answer the following questions about sourcing on Part 1 of the worksheet:

- When was this written?

- Where was this written?

- Is it reliable? Why or why not?

- Have students answer the following questions about contextualization on Part 2 of the worksheet:

- What was happening at the time? Explain the historical context.

- How did the historical context affect the content of the source?

- Have students choose three texts from Out of the Desert to analyze. Tell students that a text can be a poem, essay, letter, or drawing.

- Have students record the title, author, and type of text for each of the texts on the top 2 rows of Part 3.

- Have students complete Part 3 by doing a close reading of each text and answer:

- What is the central message of the text?

- How does the language indicate the author’s perspective?

- What does the language tell us about the author?

- What does this text tell us about life in Poston Incarceration Camp?

- Have students complete Part 4 to answer this prompt: Together, what do the three texts you looked at tell us about life in Poston Incarceration Camp?

- Have students share their Primary Source Analysis with a partner. Have partners identify common themes, language, etc. from their selected texts and analyses.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students: What patterns emerged from your analysis of the primary sources? What are the similarities? What are the differences and what accounts for the differences?

Children play basketball as part of an athletic event to commemorate the New Year in 1943. Japanese American students from the Poston school and Native American students from the Colorado River Indian School had little contact, but there were occasional basketball games played together.

Credit: Photographer: Francis Stewart, 1943. War Relocation Authority. Library of Congress. (No known restrictions on publication.)

Activity 5: Close Reading on Native American Perspective

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Close Reading of Excerpt from Sharing a Desert Home.” Tell students that they are going to read an excerpt multiple times in order to gain insight on the experiences and perspectives of Native American students living on the CRIR during World War II.

- Have students complete the “First Reading #1” section in the worksheet. Have students read the text and annotate by highlighting or underlining key information.

- Have students record key ideas in their own words in the left column.

- Have students record any questions they may have in the right column.

- Give students a few minutes to answer any of the questions they have by consulting the lesson essay, looking up vocabulary words, or asking each other.

- Have students circle any unanswered questions.

- Have students read the questions under the “Second Reading #2” section. Tell students that these questions focus on comprehending the text and the answers can be found in the text. Then, have students read the text a second time. Have students write down their responses to the following questions using the text:

- How did writing by Japanese American students differ from writing by Native American students?

- What did Native American students write about in their school paper?

- How did the CRIT student quoted in the second paragraph view the Japanese American farmers?

- What circumstances allowed the school to subjugate school land for farming?

- What does the author mean by, “The two schools – Poston and the Colorado River Indian School – were in close proximity, but seemed worlds apart as the students wrote of their separate realities.”? What is the author trying to convey?

- Remind students that they need to support all their responses with textual evidence.

- Have students read the questions under “Third Reading #3.” Tell students that these questions focus on interpreting and making sense of the text. Then, have students read the text a third time. Have students discuss the following questions with a partner:

- What is the purpose of this excerpt?

- How does it add to what you have learned in this lesson?

- Why do you think the author included the quote from a CRIT student’s writing (in the second paragraph)?

- The author wrote, “In both cases, however, Caucasian teachers or administrators had the final say in how each paper was compiled.” Why do you think this was the case? How might this have impacted the published papers?

- Have students return to their unanswered questions to see if they have now been answered. Allow students to pose any unanswered questions to the group and facilitate a discussion around those questions.

- Tell students the following: “Just as Japanese American students at the Poston school were recording their experiences, Native American students at the Colorado River Indian School wrote about their experiences in their school paper, the Colorado River Star. However, archives of this paper are not currently accessible.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following question:

- What are the reasons why these archives would not be available?

- Why is it important to preserve such archives?

- How can today’s generations preserve the past and the present for the future?

- Why is preservation especially important for marginalized communities?

Activity 6: Analyzing Primary Source: Native American Perspective

- Tell students the following: “One way to learn about the experiences of Native Americans on the CRIR is by studying oral histories. In 1972, California State University, Fullerton (CSUF) launched the Japanese American Oral History Project (JAOHP) and interviewed various people involved in or impacted by the incarceration camps. On April 8, 1978, CSU Fullerton student David A. Hacker interviewed Agnes Savilla, a Mojave Indian who was born and raised on the CRIR, about her experience living near Poston Incarceration Camp during World War II.”

- Have students read the oral history interview between Agnes Savilla and David A. Hacker and complete the worksheet entitled, “Primary Source Analysis: Interview with Agnes Savilla.”

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the following questions:

- What new information did you learn from the oral history interview?

- What are the limitations of oral history? Is the oral history interview reliable? Why or why not?

- Why is it important to hear the experiences of Native Americans living on the CRIR during World War II?

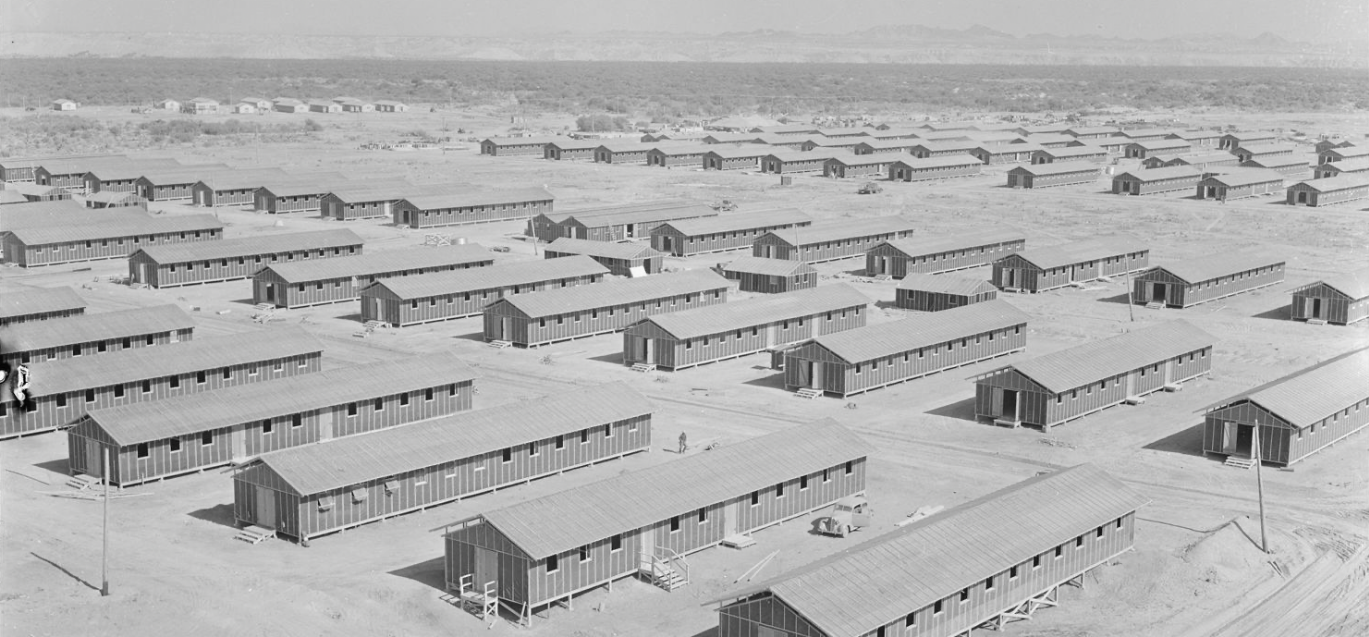

Living quarters at Poston Incarceration Camp.

Photographer: Fred Clark, 1942. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Activity 7: Comparing Life at Poston

- Show students a clip [1:16-3:33] from the video entitled, “Poston Incarceration Site.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How were the experiences of Japanese American incarcerees similar to the experiences of Native Americans?

- In what ways did the CRIT benefit from Japanese American incarceration?

- How might the Japanese American incarcerees have benefited from the CRIT?

- Have students write an essay addressing the following prompts:

- What were the experiences of Japanese Americans at Poston?

- What was Poston like before being turned into an incarceration camp? How did incarcerated Japanese American laborers impact Poston? How did this enable Native Americans to later live on this land?