Japanese American incarcerees stand in line at the departure station, waiting to leave Poston Camp.

Photographer: Hikaru Iwasaki, 1945. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Grade: 9-12Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Lessons/Activities: 6

Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944), most Japanese Americans were free to leave Poston Incarceration Camp after January 2, 1945. (At the end of World War II [1939-1945], all Japanese Americans were allowed to leave.) The Endo case allowed the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) to move forward with its “colonization” program at the Colorado River Indian Reservation (CRIR). As Japanese Americans began to move out, Hopi “colonists” began to move in. In this lesson, students will unpack the term “colonize” and learn about the colonization program that took place at Poston after World War II. Students will examine the implications of historical freedom denied for Native Americans and its implications for Japanese Americans in the narrative film, The Blue Jay. Students will reflect on the heritage of Poston and learn about the relationship between the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) and Japanese Americans post-WWII to the present.

Students will:

- Examine the history of the “colonization” program at Poston Incarceration Camp after World War II.

- Assess the motivations of the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) Tribal Council for opposing an incarceration camp on their reservation.

- Discuss the legacy of Poston Incarceration Camp.

Poston After World War II Essay:

On December 18, 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that, based on the decision

Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944), Japanese Americans could no longer be detained in

incarceration camps and were free to leave after January 2, 1945. In their decision, the Supreme Court unanimously held that the War Relocation Authority (WRA) could not continue to confine Japanese Americans who were “concededly loyal” meaning they properly answered the “loyalty questionnaire.” The questionnaire required incarcerees to affirm their allegiance to the United States and agree to service in the U.S. military if ordered to. (Those who were deemed disloyal were sent to Tule Lake Incarceration Camp, which did not close until March 20, 1946.) Although the

Ex parte Endo case did not weigh in on the

constitutionality of incarcerating Japanese Americans, it did allow Japanese Americans to leave the camps and return to the West Coast.

With the anticipated departure of the Japanese American incarcerees, the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) could now move forward with their long-awaited colonization* program. The OIA had been planning the colonization program since establishing the Colorado River Indian

Reservation (CRIR) in 1865. Its goal was for thousands of Native American tribal members to live and work on the reservation. The OIA planned to recruit tribes living along the Colorado River. The establishment of

Poston Incarceration Camp, referred to as the

Colorado River Relocation Center by the U.S. government, as a site for Japanese American incarceration during World War II (1939-1945), provided the necessary funding and labor to move their plan forward.

The OIA created an official document, “

Ordinance No. 5–Reserving a Portion of the Colorado River Indian Reservation for Colonization,” to outline the terms of the colonization. The ordinance stipulated that Native Americans who lived on tribal land where water resources were inadequate could move to CRIR. The

tribes living along the Colorado River

tributaries at the time included the Huyalapai, Hopi, Navajo, Apache, Zuni, Papago, Supai, Yuma, Chemehuevi, and Mohave. On February 3, 1945, the CRIT Council signed Ordinance No. 5, giving its official approval to allow for the colonization of other southwestern Native Americans to Poston. However, in the early 1950s, the CRIT Tribal Council challenged the validity of the ordinance, arguing they had been forced to sign it. Negotiations between the CRIT Tribal Council and OIA continued until the mid-1950s, as the two groups disputed over who owned the legal

title to the reservation land. In 1964, the legal title to the CRIR was finally settled in favor of CRIT. This was a win for the Native American community whose land has been forcibly stolen by the United States for centuries.

While these negotiations were happening, Ordinance No. 5 was in effect and the colonization program was underway. The OIA worked to recruit Native Americans to relocate to Poston with promises of land to farm, abundant water, and housing. Many Native Americans were reluctant to leave their

ancestral lands and relocate to Poston. They did not want to give up their own lands, even if it was dry. Those who did move were motivated by more fertile farming land. The colonization program officially began with the first arrival of Hopi colonists on September 1, 1945. At the time, several hundred Japanese American incarcerees were still living in the Poston camps. They were packing and making arrangements to leave Poston. When the Hopi families arrived at Poston Incarceration Camp, they moved into barracks that had just been vacated by Japanese Americans. Many Japanese Americans left their dishes, furniture, and other items in the barracks.

During the ten years (1945-1955) in which the colonization program was in effect, many other Native Americans from different tribes arrived at Poston. Many eventually returned to their former reservations to reunite with family or community, or were otherwise dissatisfied with life on the CRIR. A large number of Hopi and Navajo colonists stayed and became members of the CRIT. Today, the official seal of CRIT contains four tribes: Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Navajo. Agriculture is the main business on the CRIT land. Some CRIT members are independent farmers, and others

lease their farmland to non-Native farmers. They use the irrigation system built by the Japanese American laborers to produce cotton, alfalfa, wheat, feed grains, lettuce, and melons.

The adobe school buildings built by Japanese Americans were used by CRIT and the Parker School District until 1980. While some of the adobe buildings have been demolished, others still stand today.

Since the 1980s, many Japanese Americans who were incarcerated at Poston have visited the site. They have formed friendships with CRIT members and undertaken several programs and projects together. In 1992, several former incarcerees and CRIT members worked together to plan and build the Poston Memorial Monument. The monument was designed by Ray Takata (1934-2006), an architect, and Stephan Hamamoto (years unknown), a civil engineer. Former incarcerees, Ted Kobata (1924-2016) and Jim Namba (1923-2021) from Sacramento, built the Poston Memorial Monument dedicated in October 1992. The concrete single column monument symbolizes “Unity of Spirit.” It has a hexagonal-shaped base that represents a Japanese stone lantern. The Poston Memorial Monument is an important symbol. It serves as a reminder to those who live on the CRIR, and others who pass by, to never forget the experiences endured by the Japanese Americans incarcerated there, the injustices they faced at the hands of their own government, and the contributions they made to the community there.

The connections that bind the CRIT and Japanese American incarcerees together is fittingly inscribed and exhibited on the monument’s bronze plates. While these two groups had little contact during World War II, in the years since, they have formed a connection rooted in their shared

disenfranchisement. Though the CRIT was unable to stop the incarceration of Japanese Americans on their reservation, they spoke up in opposition to their land being used to unjustly detain another group, knowing what it was like to be forcibly relocated by the U.S. government. These two disenfranchised groups of people shared a desert home for a brief period of time. Through their relationship, the CRIT Tribal Council and Japanese Americans now share their histories for the public to observe, reflect on, and appreciate.

This text is an excerpt from the “Sharing a Desert Home: Life on the Colorado River Indian Reservation” by Ruth Y. Okimoto. It has been adapted for reading accessibility and clarity. Access to the original text can be purchased through the Poston Community Alliance.

*In “Sharing a Desert Home,” Okimoto includes the following footnote in regards to the use of the terms “colonist” and “colonization”: “U.S. government officials in the 1940s used the term ‘colonists’ or ‘colonization’ without, it seems, any thought to the meaning or impact on the CRIT community. For American Indians, the words ‘colonists’ and ‘colonizaiton’ are laden with meanings of deprivation, ethnic genocide, loss of freedom, and loss of land. Although the dictionaries vary in their definition of ‘colonist’ or ‘colonization,’ the popular or general meaning ascribed to the word ‘colonist,’ for example, is when a group of people arrive to ‘take over’ a territory and dominate the land and its indigenous people. The U.S. government officials may have used the word ‘colonist’ to mean ‘an original settler or founder of a colony.’ Or defined a colony as ‘a group of people with the same interests or ethnic origin concentrated in a particular area.’ However, the term sounds strange and inappropriate in its application to the CRIR. It is inappropriate because the geographical area has been occupied for centuries by the Mohave tribe. In addition, the Japanese American detainees were prisoners, not willing colonists eager to settle a new territory. For the purpose of this article and to be true to the historical government records, I am applying the terms as they were recorded and used. I invite the readers to keep the time period and historical context in mind.”

Bibliography:

Okitomo, Ruth Y. (2001). Sharing a Desert Home: Life on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books.

- Adobe: a building material used to make bricks

- Ancestral: of, relating to, or inherited from an ancestor, one from whom a person is descended

- Colorado River Relocation Center: the term used by the War Relocation Authority to identify the Poston “internment site” to detain Japanese Americans

- Constitutionality: the quality or state of being constitutional

- Disenfranchised: deprived of some right, privilege, or immunity

- Incarceration: confinement in a jail or prison

- Irrigation: the watering of land by artificial means to foster plant growth

- Lease: to rent out a piece of land or property for a specified term and for a specified rent

- Ordinance: a law or regulation

- Poston Incarceration Camp: the term currently used for the “Colorado River Relocation Camp” to convey that the camps were concentration camps where U.S. citizens of Japanese descent were denied due process, freedom, and their Constitutional rights

- Reservation: a federal Indian reservation is an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe.*

- Title: a legal right to the ownership of property

- Tribe: a social group composed chiefly of numerous families, clans, or generations having a shared ancestry and language

- Tributaries: a river feeding a larger river

- What did the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944) say?

- What was the Office of Indian Affairs’ colonization program?

- What was Ordinance No. 5?

- Why were Native Americans reluctant to relocate to Poston Incarceration Camp? What motivated those who relocated?

- How did Native Americans benefit from the labor of Japanese Americans incarcerated at Poston?

- What is the significance and symbolism of the Poston Memorial Monument?

- How have friendships formed between CRIT members and formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans? What is the significance of these friendships?

While incarcerated at Poston Camp, Japanese Americans built adobe school buildings. These buildings were later used by the Colorado River Indian Tribe.

Photographer: Francis Stewart, 1943. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Activity 1: Examining Parallels Between Native Americans and Japanese Americans

- Have students review learning from Lessons 1 and 2 by discussing the following questions:

- What were the original goals of the Colorado River Indian Reservation (CRIR)?

- How was the establishment of the Poston Incarceration Camp intended to help reach these goals?

- How did Japanese American labor set the site up for use after the end of the war?

- Have students watch a clip [0:30-5:37] from the video entitled, “Sharing a Desert Home.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What parallels does Dennis Patch draw between the historical experiences of Native Americans and Japanese Americans?

- In what ways did the Colorado River Indian Tribe benefit from the labor of Japanese Americans incarcerated at Poston Incarceration Camp during WWII?

Activity 2: Analyzing The Blue Jay - Part 3

- Have students recall their takeaways from Part 1 [0:00-5:16] and Part 2 [5:16-9:54] of the film from Lessons 1 and 2.

- Show a clip [9:55-13:27] from the film, The Blue Jay.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why does Pohache help Sam and his family?

- What does Pohache mean by “Indigenous people can’t trespass” (11:18)?

- What does the blue jay represent in the film?

- What message is the filmmaker trying to convey?

- How does the film introduce Constitutional rights? What do you think is the intention?

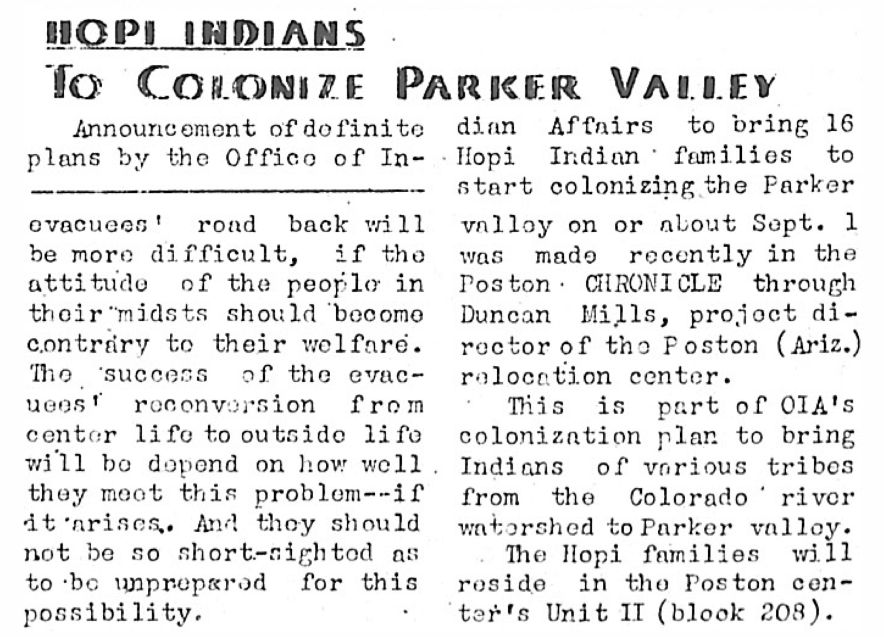

This article entitled, “Hopi Indians to Colonize Parker Valley,” was published on August 22, 1945 in The Granada Pioneer, the camp newspaper of the Granada “Relocation Center” (also known as Camp Amache), an incarceration camp in Colorado.

Credit: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, via Densho (Public Domain)

Activity 3: Unpacking the “Colonization Program” at Poston

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Discussion Questions listed above.

- Remind students that in Lesson 1 they learned that one of the U.S. government’s goals with the establishment of the CRIR was to “colonize some 10,000 Indians,” and that building Poston as an incarceration camp during WWII was intended to help them reach that goal.

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Unpacking the Term ‘Colonize’.”

- Have students write what they think the term “colonize” (and related words such as colony, colonist, and colonization) means in the row labeled, “Your perspective.”

- Have students look up several dictionary definitions of the term and write common phrases, concepts, and words in the row labeled, “Dictionary definition.”

- Ask students, “What might the term ‘colonize’ mean from the perspective of the U.S. government?” Have students record ideas in the row labeled, “U.S. government perspective.”

- Ask students, “What might the term ‘colonize’ mean from the perspective of the CRIT, or Indigenous Peoples more broadly?” Have students record ideas in the row labeled, “CRIT perspective.”

- Ask students, “What might the term ‘colonize’ mean from the perspective of incarcerated Japanese Americans?” Have students record ideas in the row labeled, “Japanese American perspective.”

- Have students read the endnote by Ruth Y. Okimoto.

- Tell students the following: “An endnote is a text feature frequently used in academic writing. Endnotes are generally placed at the end of a text and marked within the main text with a superscript number or symbol. Endnotes can provide citations to other sources, or they can provide additional information, context, discussion, or explanation that the author decided does not fit into the main text.”

- Read the endnote out loud. Annotate if needed.

- Have students add additional ideas to the worksheet entitled, “Unpacking the Term ‘Colonize’.”

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Do you agree with the U.S. government’s use of the term “colonize”? In what ways is this term accurate? In what ways is this term inaccurate? What term(s) might be more accurate?

- Why did the United States want to “colonize” the CRIR?

- Why were Native American tribes reluctant to move to the CRIR? (Have students consider the broader history of stolen land and forced removal.)

- Why is it problematic to colonize people?

Phillip Zeyouma, Sr. and Jr., members of the Hopi Indian Tribe, break ground in preparation for raising baby chicks. When the first Hopi families arrived at Poston Camp in September 1945, they moved into barracks that had just been vacated by Japanese Americans.

Photographer: Hikaru Iwasaki, 1945. National Archives. (Public Domain)

Activity 4: Examining History of Forced Removal and Stolen Land

- Write this question and display for all to see: Why did the CRIT oppose the incarceration of Japanese Americans at Poston Incarceration Camp?

- Have students respond to this question based on their learning so far.

- Tell students the following: “To better understand why the CRIT opposed the incarceration of Japanese Americans at Poston, we need to understand Native Americans’ history of stolen land and forced removal.”

- Divide students into three groups and assign one video to each group:

- Group 1: Native tribes have lost 99% of their land in the United States

- Group 2: Why It’s Time To Give Native Americans Their Land Back

- Group 3: Landback Movement: Reclaiming Tribal Land

- Distribute the worksheet entitled, “Video Viewing Guide.” Have students complete the worksheet as they watch their video.

- Have students write the title, creator, and date of release in the top boxes.

- Have students list what they heard, saw, realized, and wondered in the middle boxes.

- Have students list the central ideas of the video in the bottom box.

- Have students consider the perspective, purpose, and potential biases of the video by answering the following questions on the second page:

- What is the claim being made in the video? What is the argument?

- What is the purpose of the video? Is the video trying to persuade you of something?

- Who is the source? How does that impact the content? What info is missing (if any)?

- Have students respond to this question at the bottom of the worksheet: How does the perspective, purpose, and potential bias inform your understanding or interpretation of the information presented in the video?

- Have students form groups of three with one student representing each video. Have each student present what they learned from their assigned video and share their Video Viewing Guide.

- Reconvene as a whole group and facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How have people and politics impacted land in the United States?

- How do Indigenous perspectives of land differ from U.S. capitalist perspectives of land?

- How do these different ideologies affect people’s treatment of land and resources?

- Return to the question posed at the beginning of the activity: Why did the CRIT oppose the incarceration of Japanese Americans at Poston Incarceration Camp?

- Ask students: How does the history of forced removal and stolen land endured by Native American peoples add to your understanding of why the CRIT opposed Japanese American incarceration at Poston?

In 1992, several former Poston incarcerees and CRIT members worked together to plan and build the Poston Memorial Monument.

Photographer: Ted Kobata

Activity 5: Reflecting on Poston’s Heritage

- Divide students into two groups. Assign each group to one of these prompts:

- Group 1: “What were the consequences of the U.S. government’s decision to build Poston Incarceration Camp on the CRIR? How and why were Native Americans and Japanese Americans pitted against each other?”

- Group 2: “How have Japanese Americans and Native Americans worked together since World War II to preserve Poston’s heritage? What lessons about cross-cultural solidarity can we learn from this friendship?”

- Have students in each group meet to discuss their responses to the prompt and have them come up with an executive summary of their claims.

- Have each group present their executive summary to the class. Have students in the other group take notes and ask questions as each group presents.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- What is the legacy of Poston Incarceration Camp?

- Why is it important to learn about the history of Poston Incarceration Camp?

Activity 6: Connecting to Your Personal Story

- Have students write a Quickwrite in response to the prompt, “How does what you learned in this unit connect with your personal story?” Tell students that their personal story may involve lived experiences, family or community history, worldview, perspectives, values, etc.

- Post these four topics in four corners of the classroom:

- Promoting cross-cultural solidarity

- Exercising rights in a democracy

- Engaging in intercultural communication

- Dealing with stereotypes

- Tell students that this unit touched on these four topics. Have students choose one topic that resonates with them the most and go to the corner of the classroom with that topic.

- Have students discuss the following questions while stationed at each corner:

- What does this topic mean to you? What does it look like in your everyday life?

- How does what you learned in this unit connect to this topic?

- What actions can you take to address this topic in your community?

- Have students re-present their story in art or digital form (i.e., artwork, video, written memoir, etc.).

- Have students learn about the Poston Pilgrimage hosted by the Poston Community Alliance. Have students discuss: What are the goals of the pilgrimage? Who is the intended audience? What is the significance of the pilgrimage?

- Have students research modern day issues related to Colorado River water rights, including Native American tribes’ rights to the water. Have students identify the main problem and proposed solutions. Have students compare and contrast Native American tribal rights related to Colorado River water rights today to Native American tribal rights during World War II.

- Have students learn more about how Indigenous communities throughout the United States were impacted by Japanese American incarceration during WWII. Have students read the article entitled, “How Japanese American Incarceration Was Entangled With Indigenous Dispossession.”

- Have students further research the cases Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944), and Korematsu v. United States (1944), which were decided on the same day. Have students learn about the background of each case, the issues addressed, the court’s decisions, and each one’s legacy. Have students discuss how the two cases were at odds with each other.